Jon and DiCo

Jonathan Conyers tells the story of the debate teacher who helped transform his life. The relationship that Jon and DiCo developed has served as the basis for an organization transforming the lives of thousands of kids through debate.

1.

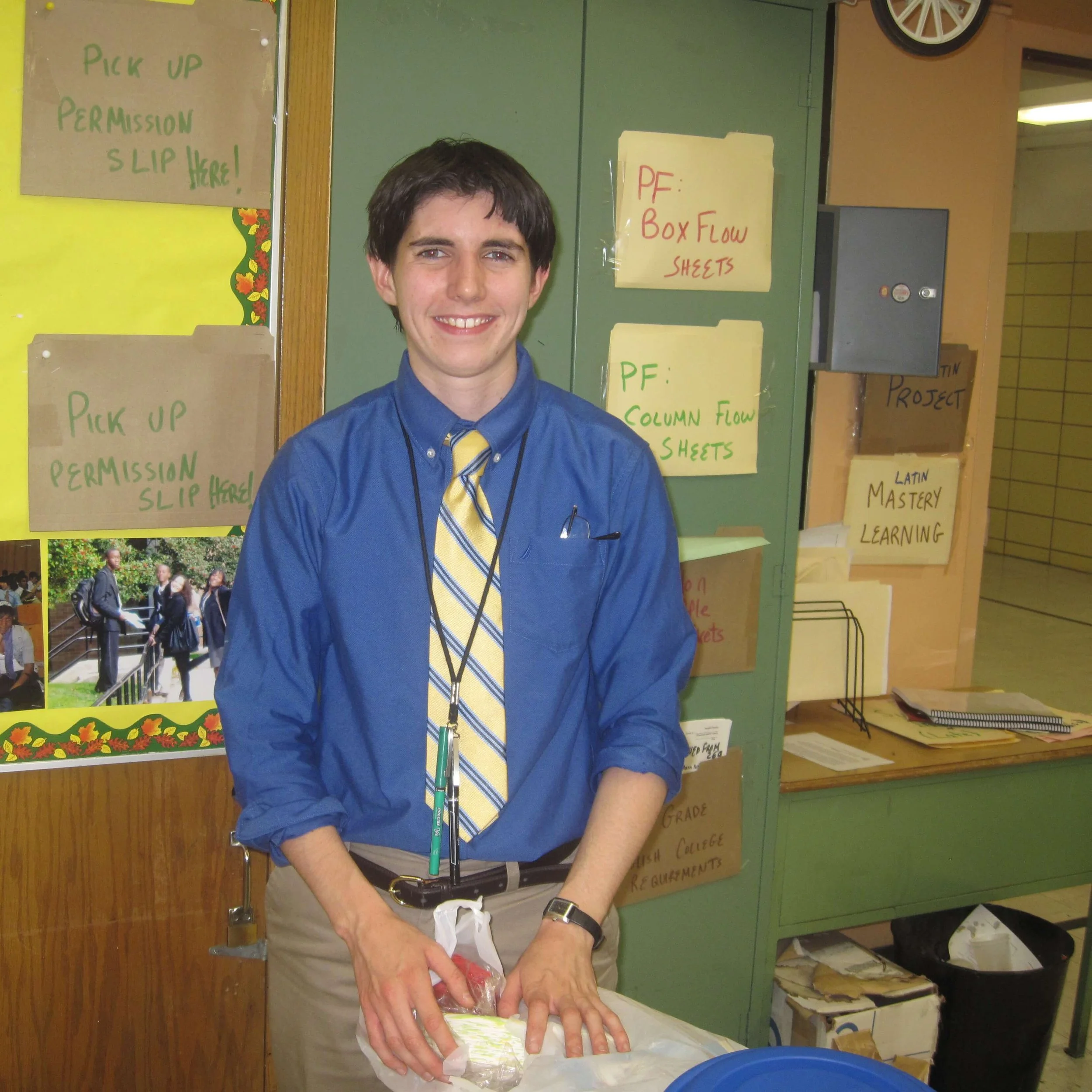

There wasn’t no plan really. I’m walking down the street with my best friend Koreh, and we see this house. And Koreh’s like: ‘Yo. Let’s break in.’ And I’m a stupid eighth grader—so I agreed. We climbed in a window and started grabbing whatever we could. The police were waiting for us when we came out. It wasn’t like the movies. They were respectful, but it was a lot of pressure. They put us in two different rooms. They’re like: ‘Koreh is telling us everything.’ My grandmother shows up, and she’s like: ‘Tell them what they want to hear.’ I didn’t know what to do. But eventually the detectives come in, and they’re like: ‘You can go. Your friend said you didn’t do nothing.’ Koreh got sent upstate to juvenile detention, and I went off to high school. Frederick Douglas Academy was known as the school you wanted to go to if you were a black boy. It was on 148th Street in Harlem, and it was run by this legendary principal named Dr. Hodge. On the first day of class he sat me down in his office, and said: ‘I know about your friend Koreh. And I know you’ve been in the system. So I want you to choose an after-school activity, and I’m going to follow you around until you do.’ For the first few weeks I just wandered the halls. The only choices were things like robotics, or math club. All of it looked boring to me. But I kept running into Dr. Hodge, and he’d be like: ‘You gotta choose something.’ So one day I wandered into the debate room, and sat down in the back. The coach was this white lady-- at least she was a lady at that time. Her name was Ms. DiColandrea, but everyone called her Ms. DiCo. She was very young. She still looked like a kid. But every time she opened her mouth, it was power. She kept asking these deep questions, like: ‘What is a good person?’ I started coming back day after day, but I never participated. I just sat in the back and listened. But one day they were discussing drug addiction, which is a topic I know a lot about. So I stood up and shared my story. Afterward Ms. DiCo asked me to stay behind. Mainly she just wanted to make sure I was OK. She was like: ‘Do you need anything?’ But after that, she was like: ‘You should join debate.’

2.

I tried to stay friends with Koreh when he came out of prison, but he was full blown. He didn’t seem like a kid anymore. There weren’t as many jokes. It was always: ‘What’s the next move? What’s the next play?’ He started saying crazy stuff, like: ‘If you want to be with me, you’ve gotta hold this gun.’ And he’s getting annoyed with me. Cause I’m like: ‘I can’t do this, bro.’ By that time I had my geek squad. These was cool kids on the debate team. A couple of the seniors were getting full rides to Ivy League schools. Debate seemed like it could be my ticket out. Some days we’d be in practice for four hours. In the beginning I was inconsistent. I didn’t like to research. So if the topic was about taxes or something, I’d do OK. But if it was personal—if it was ‘poor people this,’ or ‘drug addicts that,’ I’d destroy. On weekends we were going to tournaments all over the state. Nobody ever came to see me compete. My mom would keep saying: ‘I’m gonna be there baby,’ but she never came. At baseline my parents are the nicest people ever. But they were never at baseline. Ms. DiCo would give me these articles on drug addiction, and she’d be like, ‘Your parents do love you. They aren’t bad people. Let’s read this together.’ If she ever saw that my clothes were wrinkled, she’d offer to wash them. And when I didn’t have any money, she’d cover my tournament fees. Ms. DiCo knew that home was hell for a lot of us, so some nights she would stay until 8:30. She taught us how to focus and study. Don’t get me wrong—we was kids, so there was a lot of jumping on tables and stuff like that. But I got to where I could read twenty pages in fifteen minutes. At night I’d go home and stand in front of the mirror with pencils in my mouth—just to practice my articulation. Ms. DiCo had this quote that she loved, from Victor Frankl: ‘He who has a why can endure almost any how.’ She would say it at the beginning of every practice. Some nights when we were finished she would take me out to pizza, and she’d speak life into me. She’d be like: ‘What is your why?’ I never had a good answer to that question. All I knew was that I wanted to be like Ms. DiCo.

3.

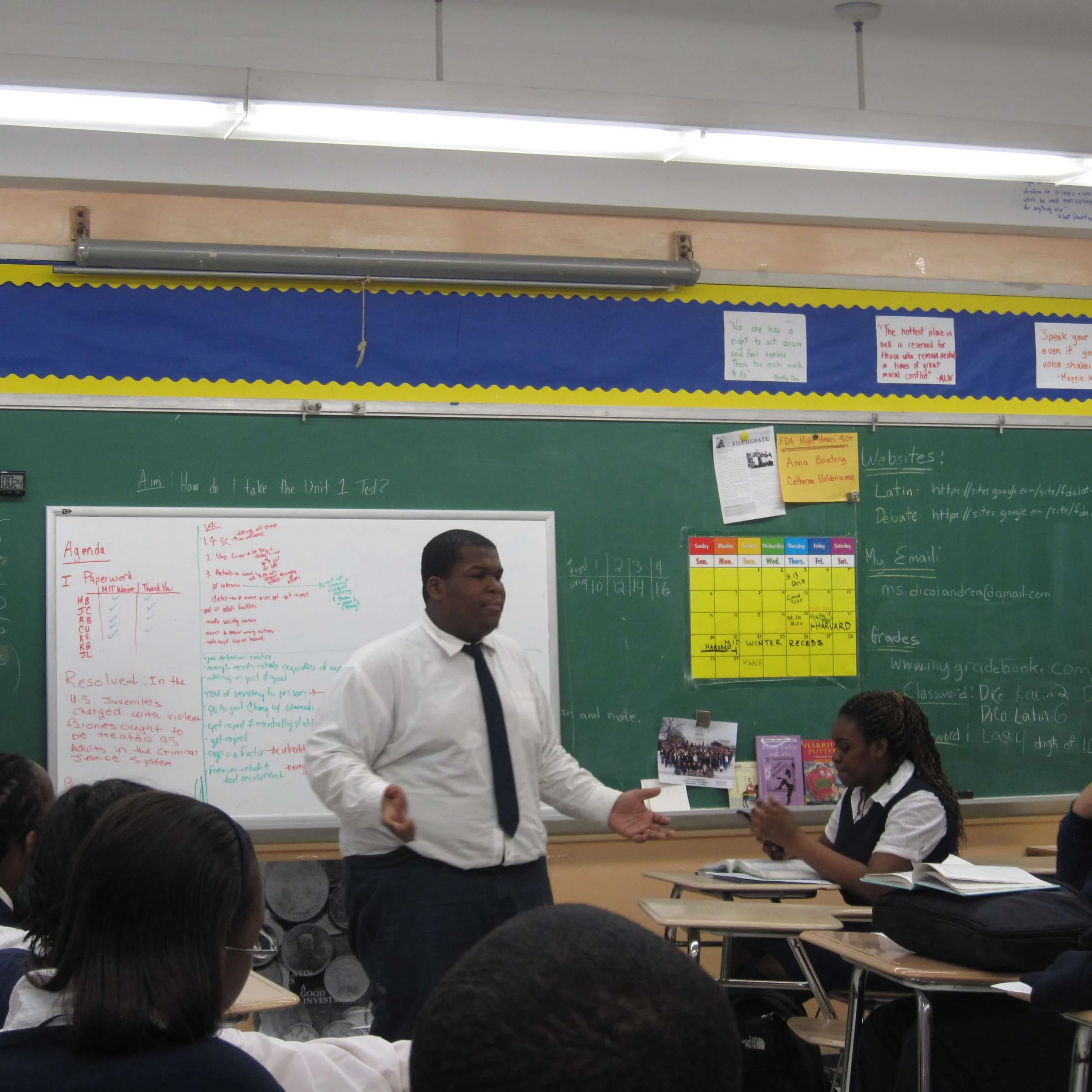

We did notice certain changes as the year went on. Ms. DiCo’s voice got deeper and deeper. Her hair got shorter and shorter. But I didn’t think much of it. To be honest I wasn’t thinking much about Ms. DiCo at all. She was white, from Manhattan. She’d gone to Yale. I just assumed she didn’t have any problems. But one morning Ms. DiCo came into class with a fresh cut, and a full suit. She seemed nervous. She walked up to the front of the room, and said: ‘This is who I am. And I hope you’ll accept me. You don’t have to call me Mr. DiCo. But I’d prefer if you don’t call me Ms. DiCo. Just call me DiCo.’ Even today I thank God that DiCo was the first person I met who was transgender. This was the only person who really loved and understood me. DiCo could have told me he was a dinosaur, and I’d be like: ‘That’s cool. Just stay DiCo.’ And the rest of the team felt the same way. A couple of the seniors gave him a hug, but then we just got back to debate. The Harvard Tournament was coming up, and it was the biggest thing we did all year. We had to sell chocolate bars just to get there. We got to stay in a hotel for three nights. It was a big deal. The topic for this year’s tournament was: ‘Should juvenile defenders be tried as adults?’ DiCo was smiling at me when he hung the topic up on the wall. He knew about my situation with Koreh. I think he thought that this would be the tournament that finally got me to focus. I started coming in early each day so we could work on my speech together. We went through a big stack of articles. We memorized the facts and statistics. And we worked on weaving in my personal story. During practice DiCo kept pushing me to the front of the class, and I destroyed. I had my speech down. I even cried a couple times, because I loved Koreh. And I wanted to prove it wasn’t fair what happened to him. At one point DiCo even got up to debate me-- which never happens. And he demolishes me. I’m stuttering, I’m struggling. It was like practicing against Tom Brady, and it pissed me off. I was like: ‘Why is DiCo doing this to me?’ But after class he pulled me aside, and said: ‘You could be the first kid I’ve had that wins at Harvard.

4.

One night I was at a talent show in the Bronx. And somebody came up behind me and grabbed the back of my head. It was Koreh. It had been almost a year since I’d seen him, and he’d changed. His voice was deeper. I could feel the presence of the people he was with. It felt like he had power. Growing up he’d never taken himself seriously. He was always dancing in class, or blurting out something stupid. The teachers gave him warning after warning. My grandmother always told me that he was a bad influence. But to be honest, she loved him too. She’d invite him in her apartment, and feed him. He’d kiss her hand. He’d be like: ‘You’re so beautiful Ms. Smith, can we read the Bible together?’ Koreh didn’t care nothing about God. But he’d turn on some gospel music, and grab the tambourine. Sometimes he would overplay. I remember one day he called Ms. Brown a ‘B,’ and the school called his emergency contact number. This tall black dude showed up and smacked the shit out of him. Right in front of everybody. I’d never seen this guy before. I’d been to Koreh’s apartment a lot of times, and I ain’t never even seen an adult. It was a potato-chips-for-dinner type situation. There were no rules. Koreh never had a curfew. If I was ever out after dark, my grandmother would come looking for me. But nobody ever came looking for Koreh. One time he stopped coming to school for a few weeks. None of us knew where he was. And when he finally came back, he told me that he’d gone to his mother’s funeral in South Carolina. He wasn’t bawling, but there were tears in his eyes. We never really talked about it again, but after that day Koreh kinda turned into a monster. It seemed like every year he’d take more and more risks. He was always involved in some kind of situation. He tried his best to keep me out of it. Even when he was selling drugs with his cousins, he’d be like: ‘Leave Jon alone. Jon’s gonna be somebody.’ But a lot of times I couldn’t help but get involved, cause we was always together. Like that time in eighth grade when we were walking down the street, and we saw this house. And Koreh’s like: ‘Yo, lets break in.’ And I’m stupid, so I agreed.

5.

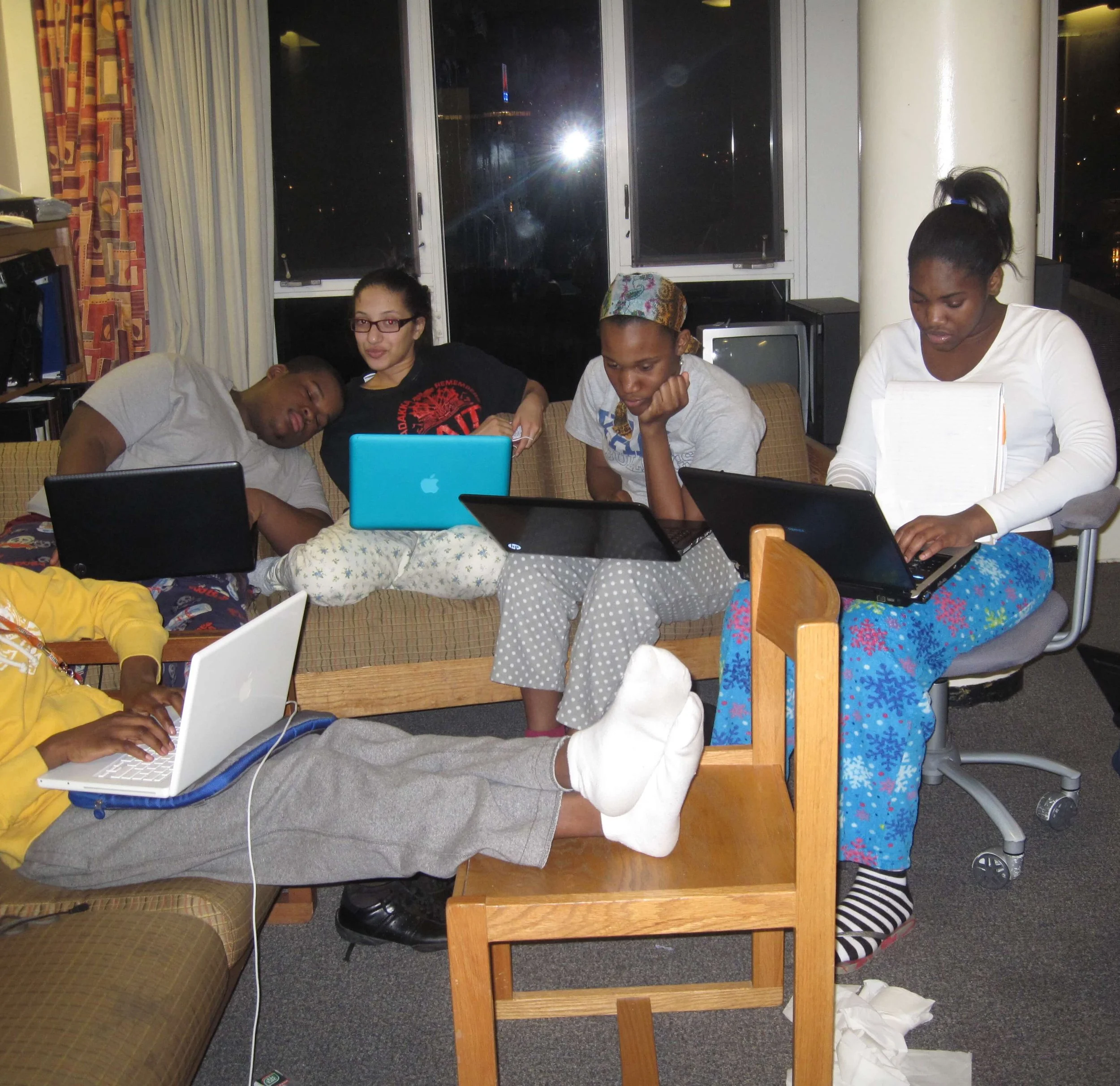

On the bus to Harvard we were cutting ass. Maybe a couple of the seniors were stressed. But the rest of us were laughing and making clown faces. That’s one beautiful thing I’ve learned in life: if your expectations are low enough, you can be completely free. I went into every tournament thinking: ‘This is impossible.’ We knew we were never going to beat these rich kids. As soon as we stepped off the bus, everyone was looking at us. It’s not every day you see a transgender teacher with all these big ass black kids. And it was very obvious that we poor. Everyone else was wearing ironed dress shirts and khakis. We’ve got plain white tees and sandals. DiCo’s trying to help us tie our ties. It was embarrassing. It’s like, c’mon DiCo. You just became a guy. Now you’re tying our ties in front of all these white people. The first place we went was the cafeteria for lunch. All these other kids were looking at their notes, and talking about their topics. We’re giving piggy-back rides and talking about Lebron. DiCo tried his best to make us focus. He’d be like: ‘C’mon guys, this is serious stuff.’ But we weren’t hearing it. On the first day DiCo was mainly watching the older kids. I was in in there all by myself, but I’m killing it. There was nothing too special about my speech. Everyone had been studying the same articles, so we were using the same facts. But at the end of every round there’s this thing called ‘Cross X,’ when you get to ask your opponent questions. And that’s when I shined. I’d talk about Koreh. I never said his name, because you can’t use names. But I’d ask if they knew what it was like to grow up without a mom or dad. Or if they’d ever eaten potato chips for dinner. I’d say: ‘‘Do you know anyone who’s been personally affected by the justice system?’’ And when they said ‘no,’ I’d be like: ‘Maybe you’re not the best one to be making this argument.’ I ended up making it past the first round. Then the second. I’m still thinking that I don’t have a chance. But after the third round, one of the judges pulled me aside. He was like: ‘You need to slow down. And have a bit more sportsmanship. But if you don’t win-- this tournament is rigged.’

6.

I went running down the hall. I hadn’t even taken time to zip up my backpack, so my papers were flying everywhere. I ended up finding DiCo in the cafeteria, and I told him what the judge had said to me. He was excited at first. But then he asked to see my scorecards, and that’s when his face changed. It started getting redder and redder. Even though I was winning, my scores were dropping each round. And all the judges were writing the same thing: ‘Jonathan needs to stick to the facts. His life story gives him an unfair advantage.’ DiCo didn’t like that at all. He told me that he was going to come watch my next round. This time I was competing against a kid from California. Another minion: khaki pants, white shirt, leather briefcase. And I ended up doing very well. I made all my points. And when the scores were being added up, both me and DiCo were feeling confident. But the judge finally stood up, and announced that I had lost. Honestly I didn’t care much. I was just happy that I’d made it so far. DiCo seemed happy too. But then he took a look at the scorecard, and it said the same shit: ‘Jonathan used his personal story too much.’ And that’s when DiCo snapped. When DiCo snaps, it ain’t like reality TV. It’s beautiful. It’s the most articulate disrespect ever. He’s using all these big words. He’s asking questions, just like he taught us. He’s saying things like: ‘You will not do this to him. These rich kids have access to every resource. But you’re penalizing Jonathan because his life is fucked up?’ But DiCo isn’t doing everything that he taught us. He always told us to control our emotions. But DiCo was getting pissed. He smacked the scorecard down on the table. He’s twitching. I think he might have called the judge a racist. I started laughing, because DiCo was acting crazy. But that made DiCo even more mad. He didn’t even speak to me when we walked out of the room. But that night when we were packing up our hotel, he was like: ‘Why aren’t you more angry? You worked so hard for this.’ And I’m like: ‘I dunno, DiCo. This is normal life for me.’ And he’s like: ‘Well, you better start caring more. Or this is going to be your life forever.’

7.

There were certain people in the building who weren’t happy about DiCo’s transition. They thought it was a distraction. When DiCo set up this after-school program for LGBT kids to come and talk, some people in the administration were like: ‘Hell no, not in the middle of Harlem.’ One of our assistant principals was a former deacon, and during a faculty meeting he mentioned ‘the homosexuality on the third floor.’ DiCo was the only gay person in the room. Even without all this extra stuff, DiCo’s transition would have been hard for anyone. He started walking around with a sad face all the time. But I never paid much attention, because I was so focused on myself. After Harvard I felt like I had something going. Next year I’d be old enough to be a captain, and our captains were getting full rides to Ivy League schools. I thought in two more years—that was going to be me. But this was also the year that Dr. Hodge retired, and things started to change at FDA. The debate team lost some of its funding. DiCo asked us to sell more chocolates. He was trying to get us to pick up the slack, but even he seemed less engaged. It’s not like he was saying ‘F these kids,’ or anything like that. But something was missing. DiCo had always been the kind of teacher who’d be enthusiastic at 6:30 AM. He was always giving us 150, but now he was giving us 90. And that wasn’t enough for me. I needed the world from DiCo. The moment he said: ‘I need a little bit more from you, I didn’t like it at all.’ One day we heard a rumor that a student had pushed DiCo down the stairs. DiCo never spoke to us about it, because he’s got this complex where he doesn’t want to see bad in anybody. But I’m pretty sure that’s when he made his decision. One afternoon he came into practice with his head down. He wasn’t looking anyone in the eye. Normally DiCo is so good with eye contact, so we knew something was up. He began to speak but he was stuttering. He looked like he was going to cry. I’m like: ‘Just say it DiCo, we can help you.’ I thought maybe someone had died or something. But then he cleared his throat, and said: ‘I’m leaving.’ And instantly I felt hate.

8.

DiCo brought in a new coach to smooth the transition. It was a black man. Maybe DiCo thought that would make things better, but it didn’t. DiCo kept trying to explain himself. He’d be like: ‘Let’s talk about it, Jonathan.’ But I gave him the cold shoulder. Or I’d say something stupid, like: ‘If there’s no debate, I’m going to drop out of school.’ DiCo leaving was just enough of an excuse for me to start doing the dumb stuff I wanted to do anyway. Koreh had gone back to prison, but a lot of my other friends were still around. We were drinking a lot, acting crazy. I didn’t even say goodbye to DiCo at the end of the year. I was hurt. I told myself a story, about how DiCo couldn’t handle black kids. And that he’d never have another team like us again. But after a few months I started getting updates from former teammates. They were like ‘Haven’t you heard? DiCo’s coaching at another black school. And he’s got another winning team.’ I didn’t even join FDA’s debate team my junior year. I didn’t have the energy. That was the year my father found out my mom had an affair, and went after her with a knife. We got evicted for the eighth time. I’d started dating a girl named Nicolette, and she lived in Brooklyn. So I was spending a lot of time in Brooklyn with her. The funny thing is Nicolette’s house was ten minutes from DiCo’s new school. So I’d walk by it every time I went to visit her. It was this beautiful new charter school. There were brownstones all around it. All these kids had uniforms. It made me mad. It’s like: Why don’t I deserve this too, DiCo? Why did you get to leave? I know you were just my teacher. But you can’t just be a teacher in black neighborhoods. Most of the time you weren’t even teaching, you was trying to save us. And I did everything you asked me to do. I became a geek. I did all these bullshit paragraphs. And then you ran away. Why don’t I get to run away too? I’m living in a box. My parents are on crack. Every day of my life I want to run away. It wasn’t fair of me to think like that—but I was hurt. I felt trapped. Then right before my senior year, I got a call from Nicolette. ‘I’m pregnant,’ she said. ‘You’re going to be a father.’

9.

I felt like my life was over. I remember pacing around my apartment, screaming that I wasn’t ready to be a father. My teachers were trying. They’d be like: ‘Jonathan, you’re basically done. Just finish the year.’ But I didn’t see the point. I missed 90 days of senior year. I didn’t even bother sending off college applications. DiCo was sending me texts. He kept being like: ‘This isn’t the end of the world. Just remember what happened at Harvard. If you go to college, a lot can happen.’ But I wasn’t giving him much access. I’m lying to him. I’m telling him that things are good, but in reality I was drinking a lot. One morning I was sitting on a bench in the courtyard, and my parents’ drug dealer walked by. He was this older dude named Q, and he’s like: ‘Why aren’t you in school?’ I explained that I had a kid coming, and I didn’t know what to do. He’s like: ‘Why don’t you take a ride with me in my car?’ We went to pick up his daughter from school, and it was clear that Q was taking good care of her. She was wearing new clothes. He bought ice cream for all of her friends. He dropped a wop of cash on the dashboard, just to make a point. For two weeks we just rode around in his car, running errands. But one day he reached over and handed me a bag. He’s like: ‘It’s time to get started.’ It wasn’t dramatic like the movies. I’d just sit on the bench. And I guess Q put the word out, because people started coming up to me asking for drugs. I’d sell for a few hours. Then at the end of each day I’d go back to the shelter and watch my parents use the exact same drugs. I was becoming everything I hated about my community. Then one morning I was sitting in the apartment, and somebody starts knocking on the door. They’re screaming that Q just got robbed, and he wants me to grab the gun from his apartment. I hesitated. It took me a few minutes to get out the door. I guess Q got tired of waiting, and went to get the gun himself. And when I finally got to his place—there were cops everywhere. Q was lying on the ground. His hands were cuffed behind his back, and the gun was lying right next to him. It was supposed to be me that was holding that gun. I’d come that close.

10.

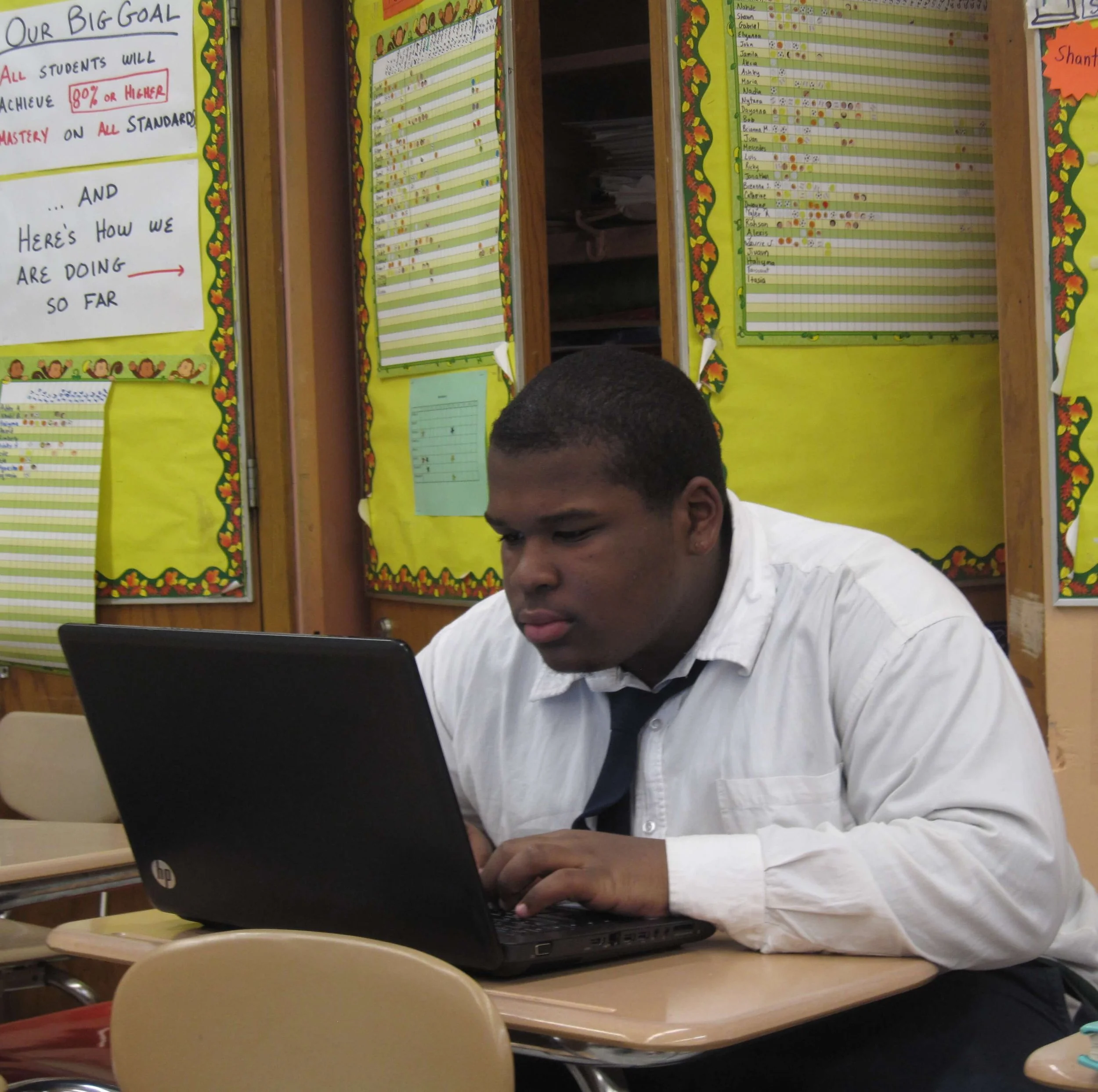

The next morning I went to school. I was still drunk, but I found my way to the counselor’s office and picked up some college applications. By the end of the week I’d sent them all off, and one month later I got an acceptance letter from Stonybrook University—with a full scholarship. They offered to pay for my dorm and everything. The first thing I did was text DiCo. He was so happy. He asked me to come visit his school and speak to his new team. He’d invited me before, but I’d always been too ashamed. Because nothing good was happening in my life. But now I had some of my confidence back. DiCo met me at the front door of the school. He was wearing a full suit, and he seemed happy. He seemed himself. He gave me a tour of the school and we ended up at his classroom. At FDA there had only been eight kids in debate. But now DiCo had 75 kids. There were extra teachers helping him. There were brand new laptops, and brand-new materials. And there were so many trophies. These kids weren’t just competing at Harvard. They were winning at Harvard. DiCo took me across the room to this wall where he’d hung up all these pictures of famous people: there was the first black astronaut, and the first Latino judge. It was called ‘The World Changer Wall,’ or something like that. And my picture was up there. Obviously I didn’t belong on that wall, but I was on the wall. This whole time I thought that DiCo had been ashamed of me. But my picture was on his wall. The bell rang and all these kids came running in. Some of them recognized me. They were tugging on my sleeve, being like: ‘Tell us the Harvard story.’ I was like: ‘You told them that?’ And DiCo’s like: ‘I told them everything. None of this would have been possible without you.’ I needed to hear that. It made me feel like what I did for those two years wasn’t lost. When the practice began, DiCo tried to make me feel like I was a part of it. Every time a kid was presenting, he’d be like: ‘Jon— how would you answer that? What would you do?’’ During one of the sessions, he pointed out a kid across the room. He said: ‘That’s you freshman year. His parents are on drugs. And I’d love if you could talk to him for me.’

11.

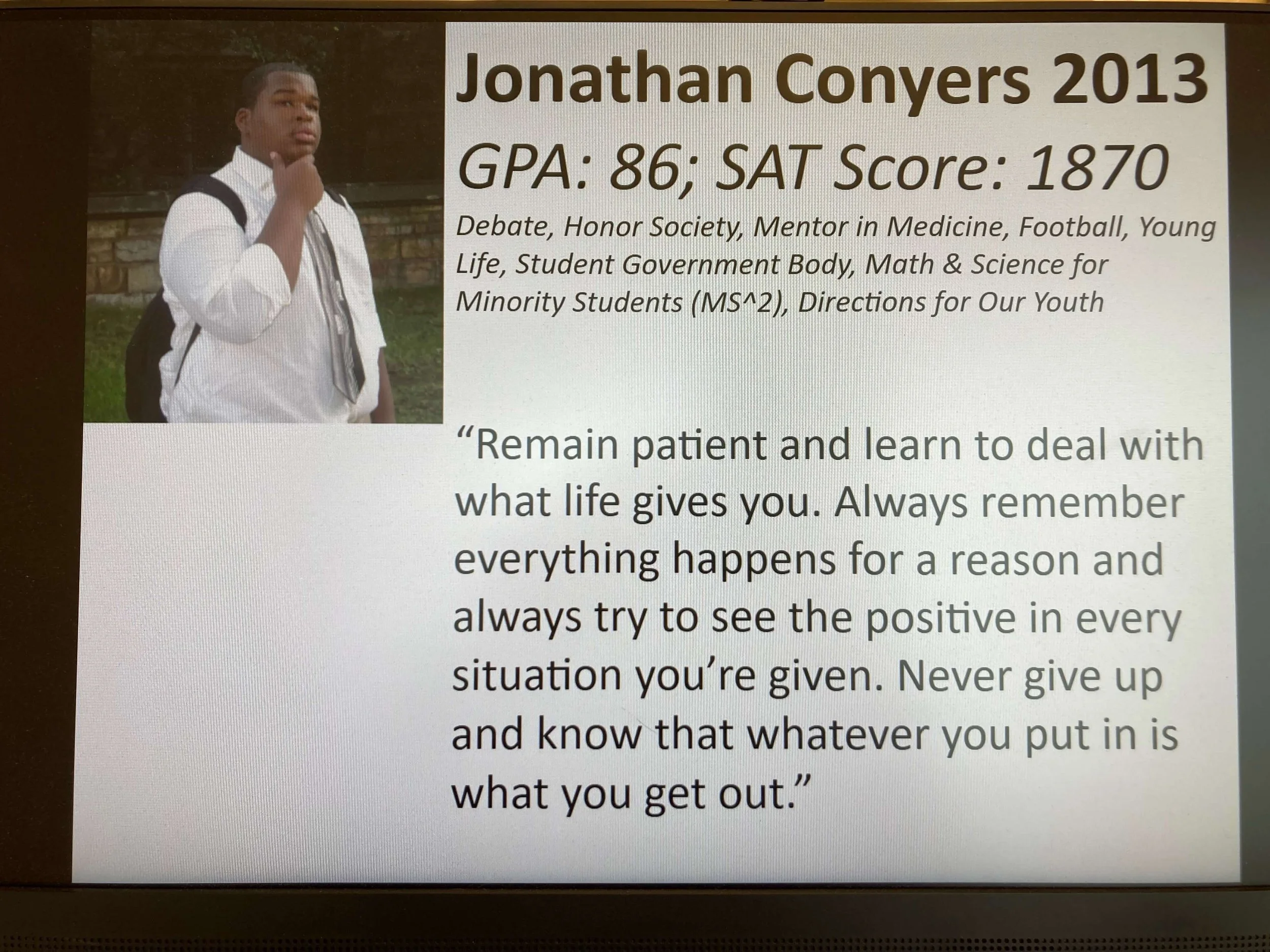

My daughter Emily was born on February 2nd, 2013. Then three weeks later I started at Stonybrook. None of it was easy. Nicollete and I struggled. She had postpartum, and I had no idea how to be a father. I slipped so many times. I self-sabotaged. But DiCo has got this parenting instinct. Whenever he didn’t hear from me for awhile— that’s when he’d show up. He’d send me money, or even just a card to say he was thinking about me. I got my GPA up to a 3.5. I ended up becoming the R.A. of my dorm. And during my junior year Stonybrook decided to highlight my story in a fundraising campaign. They put my picture up on billboards, and busses. They flew in some producers from California, and filmed a video. They made me seem so great, but self-made is bullshit. Not when you grow up like me. There were so many people who helped me. It wasn’t just DiCo. But if DiCo doesn’t come, I never get to those other people. DiCo is number one. And not just for me, either. Our whole team is doing big things. Marvin’s at Columbia law school. Armani is an actor. Jasly went to Harvard. Ksewa is a screenwriter in Los Angeles. Rollins is a director for charter schools in Connecticut. Maybe some of that happens without DiCo. But not for me. If it wasn’t for DiCo I’d have been in that cell with Koreh. I’m a respiratory therapist now, and my very first year I was making more money than DiCo. It got me thinking: ‘How did DiCo do it?’ A few years ago I asked him: ‘How could you afford to help us so much, working as a public school teacher?’ ‘I couldn’t,’ he said. ‘But I saw all of you as an investment. And I thought if I poured enough into you, you would help me give back to the world.’ A few years ago DiCo started something called the Brooklyn Debate League. He’s trying to start debate programs in urban areas: find coaches, provide resources, subsidize tournaments. At first I was just the biggest donor. But now I’m a board member, and I’m right there with him: visiting schools, giving speeches. I bet DiCo never could have imagined it. Back when I was a crazy ninth grader, jumping on tables. I bet DiCo never thought in a million years that one day we’d be coaching together.

12.

Sometimes after work DiCo will be like: ‘You wanna get a drink together?’ And that still feels weird, even though I’m 27. Because part of me will always see him as my superior. DiCo laughs at me. He says: ‘C’mon, you’re doing better than me now.’ But part of me is always gonna be a kid around DiCo. Last week we went to a vegan restaurant together. The only time I eat vegan is when I’m with DiCo. We got a couple drinks. And DiCo started telling me all these things that he’d never told me. He told me that his sister had been very sick while he was coaching our team. ‘I was visiting the hospital every day,’ he said. ‘Didn’t you wonder why I kept leaving practice early?’ I felt so bad. Because the truth is I didn’t wonder. I never sat down and wondered what it was like to be DiCo. For the first time in my life I’d found somebody that would take on my trauma, and my pain. Because DiCo was all I had. But you know what? We were all he had too. He was with us until 8:30 every night, and not once did I ask DiCo: ‘How are you doing?’, ‘How was your day?’ He was dealing with the transition, and his sister, and all this other stuff. But I only cared about me, me, me. For so many years I’d been mad at DiCo. Even when I wasn’t mad anymore, I was still sour. I kept asking myself, what if he hadn’t left? Stonybrook is great. But maybe I could have gone to Harvard like Ksewa. Or Yale, like Jasly. I put all of that on DiCo. Because that’s what hurt people do. It was easier for me to focus on DiCo leaving, instead of what he did for me during those two years of my life. Toward the end of our dinner I was crying so hard that people were bringing me water. Then DiCo hit me with one last thing. He said that as soon as he got hired by the new school, he’d gone to the principal and asked them to hold a spot for me. He called my mom. He told her: ‘Let Jonathan come with me.’ For weeks DiCo kept calling her, saying: ‘Please, it’s a great opportunity.’ But my mom never followed through. She wouldn’t fill out the papers. Because she was on drugs. ‘I didn’t want to tell you,’ DiCo said. ‘Because I never wanted you to blame your mom. But I did try. I tried to take you with me.’