Bubjan

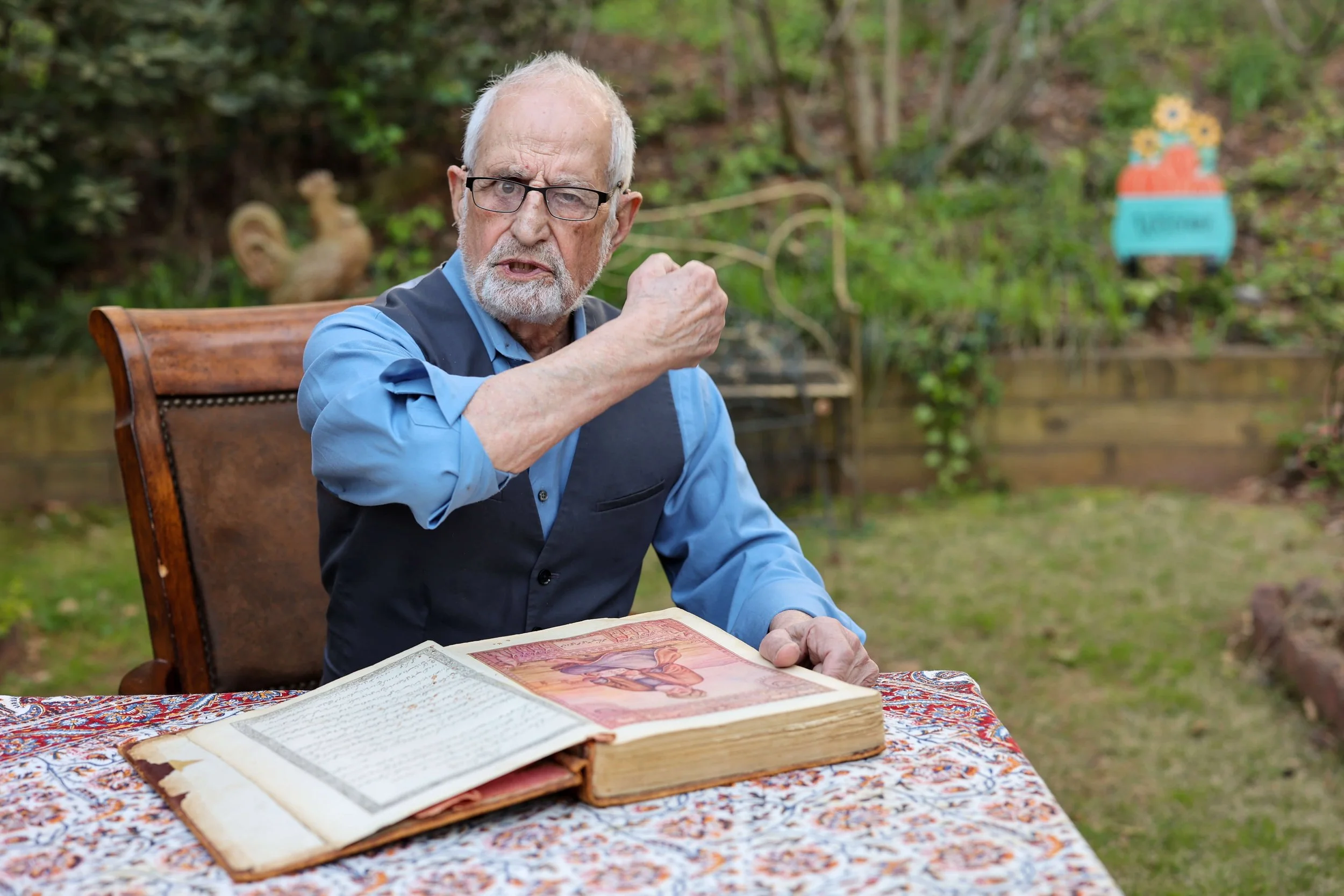

Meaning ‘Grandfather’ in Persian, Bubjan tells the story of an Iranian dissident who was exiled from the country he loves. It is a story about living one’s beliefs. Bubjan was published to coincide with the one-year-anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death, an event which sparked a sustained wave of protests in Iran.

1.

We begin in darkness. A siren screams. The invaders come from the desert in a cloud of dust. The king gathers his army at a mountain castle. A single battle decides our fate. The battle burns, the din of drums, the clash of axes, the spark of swords. The dirt turns clay with blood. The sun goes down on a fallen flag. The day is lost. The king is gone. Our people are left defenseless. The only weapon we have left is our voice. So they come for our words. Scholars are murdered, books are burned, entire libraries are turned to dust. Until nothing remains. Not even memories of who we were. Silence. The sun comes up on a knight galloping across the land. He summons the teachers, the scholars, the authors, the thinkers. He tells them to gather the words that remain: the books, the scrolls, the letters, the verses. Everything that escaped the burning pits. Then he summons the sages. The keepers of our oldest myths, from before the written word. He copies their stories onto the page. Then when all has been gathered, all of the words, only then does he summon a poet. It had to be a poet. Because poetry is music. It sinks into the memory. And in this land of endless war, the only safe library is the memory of the people. It is said that at any given time there are one hundred thousand poets in Iran, but only one is chosen. A single poet, for a sacred mission. Put it all in a poem. Everything they’re trying to destroy. The entire story of our people. Our kings. Our queens. Our castles. Our banquets. Our songs and celebrations. Our goblets filled with wine. Our roasted kebabs. Our moonlit gardens. Our caravans of riches: silken carpets, amber, musk, goblets filled with diamonds, goblets filled with rubies, goblets filled with pearls. Our mountains. Our rivers. Our soil. Our borders. Our battles. Our crumbled castles. Our fallen flags. Our blood. Who we were. Who we were! Our culture. Our wisdom. Our choices. And our words. All of our words. Three thousand years of words, a castle of words! That no wind or rain will destroy! However long it takes, put it all in a poem. All of Iran, in a single poem. A torch to rage against the night! A voice to echo in the dark.

2.

I couldn’t find it anywhere. Even on the streets of Tehran—it was nowhere to be seen. The Iran I knew was gone. Everywhere I turned it was nothing but black: black cloaks, black shrouds. The universities were closed, the libraries were closed. Our poets, our singers, our authors, our teachers: one-by-one they were silenced. Until Iran only survived inside our homes. I never planned to leave. I didn’t even have a passport. Twenty years earlier I’d sworn an oath to The Siren: every choice I made, I’d make for Iran. But The Siren was dead. They shredded his heart with bullets. And there was only one choice left: leave and live, or stay and die. It was an eight-hour drive to the Turkish border. Mitra came with me. We rode in silence the entire way. I’ve always wondered how things would have turned out differently if we’d been more aligned. She wanted our lives to be a love story. A surreal romantic journey. She wanted a life of togetherness, surrounded by beauty. For me life was meant to be lived in the pursuit of ideals: truth, justice, freedom. Even if that meant the ultimate sacrifice. We kissed goodbye in the border town of Salmas. In the main square stood a statue of Iran’s greatest poet: Abolqasem Ferdowsi. On that day it was still standing. Soon the regime would tear it down. I spent the night in the house of a powerful family who was known to oppose the regime. Their servants stood around the house with machine guns on their shoulders. Six months later they’d all be dead. On my final morning in Iran I woke with the sun. I knelt on the floor and prayed. The final journey was made on foot. It was six miles to the border, the road climbed through the mountains. It was a closed border; so the road was empty. Every step felt like death. I’ve never cried so many tears. Ferdowsi once wrote: ‘A man cannot escape what is written.’ I’ve always hated that quote. I hate the idea of destiny. There is always a role for us to play. There is always a choice to be made. But on that day it felt like destiny, a river flowing in one direction. And I was a leaf, floating on top. Away from where I wanted to go.

3.

It’s been forty-three years since I’ve seen my home. All I have left is a jar of soil. It’s good soil. Nahavand is a city of gardens. A guidebook once called it ‘a piece of heaven, fallen to earth.’ The peaks are so high that they’re capped with snow. A spring gushes from the mountain, and flows into a river. It spreads through the valley like veins. We lived in the deepest part of the valley, the most fertile part. Our father owned thousands of acres of farmland. When we were children he gave us each a small plot of land to plant a garden. None of the other children had the discipline. They’d rather play games. But I planted my seeds in careful rows. I hauled water from a nearby well. I pulled every weed the moment it appeared. As the poets say: ‘If you cannot tend a garden, you cannot tend a country.’ My garden was the best; it was plain for all to see. The discipline came from my mother. She was very devout. She prayed five times a day. Never spoke a bad word, never told a lie. My father was a Muslim too, but he drank liquor and played cards. He’d wash his mouth with water before he prayed. The Koran was in his library. But so were the books of The Persian Mystics: the poets who spent one thousand years softening Islam, painting it with colors, making it Iranian. Back then it was a big deal to own even a single book, but my father had a deal with a local bookseller. Whenever a new book arrived in our province, it came straight to our house. I’ll never forget the morning I heard the knock on the door. It was the bookseller, and in his hands was a brand-new copy of Shahnameh. The Book of Kings. It’s one of the longest poems ever written: 50,000 verses. The entire story of our people. And it’s all the work of a single man: Abolqasem Ferdowsi. Shahnameh is a book of battles. It’s a book of kings and queens and dragons and demons. It’s a book of champions called to save Iran from the armies of darkness. Many of the stories I knew by heart. Everyone in Iran knew a few. But I’d never seen them all in one place before, and in a beautiful, leather-bound edition. The book never made it to my father’s library. I brought it straight to my room.

4.

My father named me Parviz—after one of Iran’s ancient kings. His story comes at the end of Shahnameh, in the historical section. Parviz was a good king. Not a great king, but a good king. His reign was a golden age of music. But he made many mistakes. His grandson Yazdegerd would be the last king of the Persian Empire. Every day on the way home from school I’d pass by the ruins of an ancient castle, where he made his final stand against the armies of Islam in 642 AD. The Battle of Nahavand was the bloodiest defeat in the history of our country. Most days when I got home I’d go straight to my room and read Shahnameh. The book opens in myth: our oldest stories, from before the written word. But the poets say our myths are even truer than our history. They emerge from the collective psyche. They hold our dreams. They hold our ideals. When Ferdowsi writes about our mythic heroes, he writes about all of us. And in Shahnameh there is no greater hero than Rostam. The Heart of Iran. A knight with the height of a cypress. And a voice to make, the hardened hearts of warriors quake. At one point in Shahnameh Iran is on the brink of defeat. Three enemy kings have joined their forces. Our armies are almost beaten. Rostam arrives at the battlefield on foot: no horse, no armor, carrying nothing but a bow and arrow. And with a single shot he slays the greatest champion of the other side. I wanted to be Rostam. My brother and I built a gym behind our garden. We took the heads off of shovels and made parallel bars. We made barbells out of clumps of dirt. We’d wrestle sixty times a day. And while we wrestled my brother’s friend would beat a drum and chant our favorite verses about Rostam: his defeat of the demon king, his battle with the dragon. There were no dragons in Nahavand, but there were ibex. They only lived at the highest elevations. And they were beautiful with their horns. I’d climb all night. I’d make my way by moonlight. The cliffs were covered in ice, a single slip could mean death. But I’d reach the summit by dawn, and watch the sun come up on herds of ibex grazing on the peaks.

5.

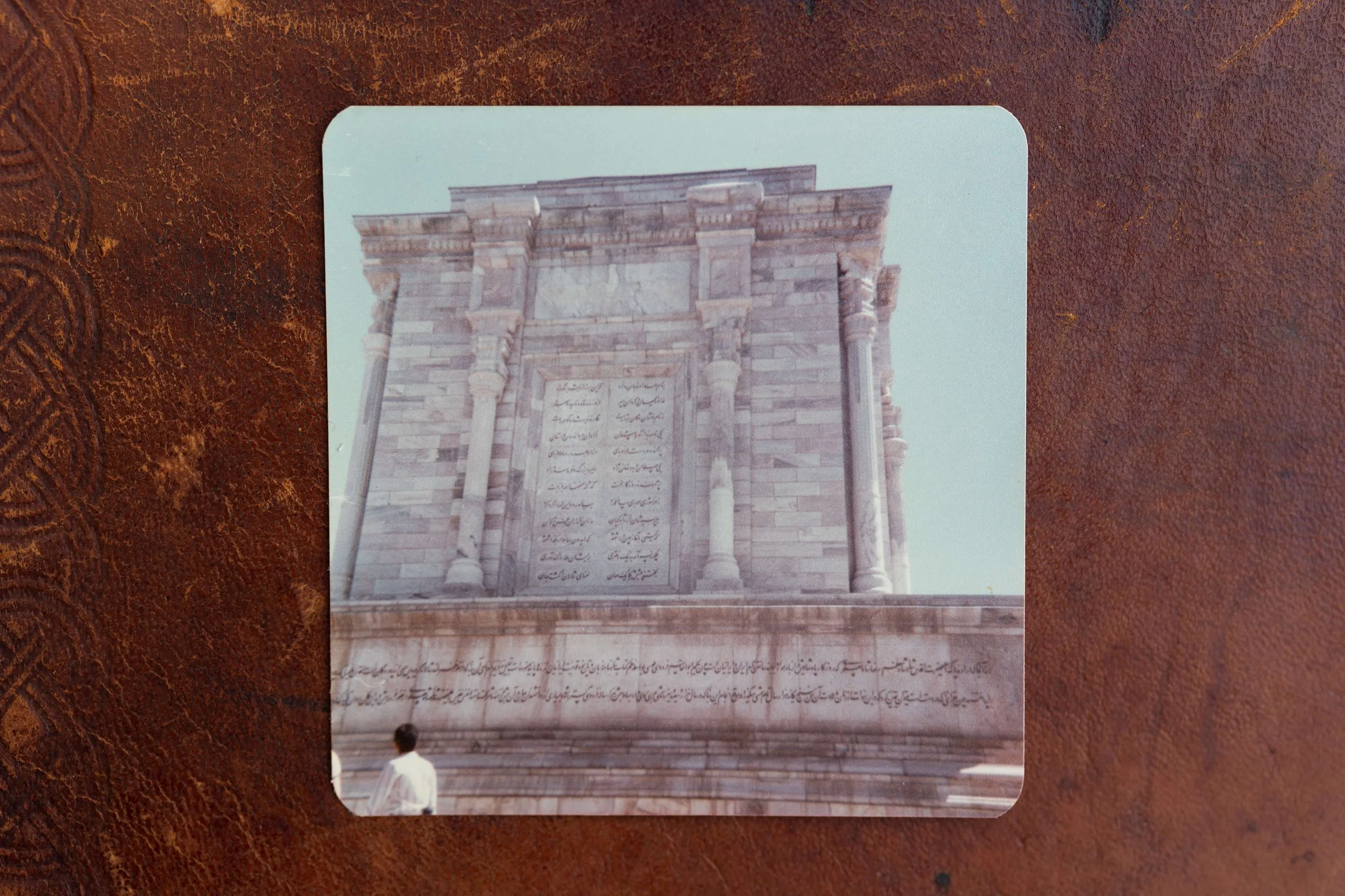

The meaning of our most important words I learned from my mother. Rasti: Truth. I never heard her tell a lie. Neeki: Goodness. I never heard her gossip. And Mehr: Love. We were three brothers and five sisters, but she loved us all equally. There were no assigned places at our dinner table. Everyone got their desired portion. While we ate our father would encourage us to debate the events of the day. No topic was off limits: history, politics, even the existence of God. And everyone was encouraged to use their voice. One weekend my father drove us all to visit Ferdowsi’s tomb in the city of Tus. It’s a large tomb. It’s modeled after the tomb of Cyrus The Great. On its face is etched the first line of Shahnameh. The master verse. The cornerstone: ‘In the Name of the God of Soul and Wisdom.’ Jaan and Kherad. Soul and Wisdom. The two things that all humans have. With the opening line Ferdowsi does away with all castes and classes. He does away with all religion. He gives everyone a direct connection to the creator. As a young boy I’d memorized hundreds of verses. One of my favorite stories in Shahnameh is when Rostam selects his horse. Rakhsh is the only horse in Iran that can carry Rostam’s weight. Rakhsh has the body of a mammoth. But he's wild, he foams at the mouth. Rostam has to fight to tame him. I was a shy child. But something happens when I read Shahnameh. There’s an epic cadence. The words demand to be spoken. It’s like touching a hot stove. I feel the heat, I feel the pressure. It’s like a sword pierces my body and I have to let it out: ‘Rakhsh roared beneath Rostam!’ The neighbors would come running to their balconies to watch. Every region in Iran has its own dialect, and I could switch between them. The language is ancient, so I didn’t know the meaning of every word. But I could feel the music. When I mispronounced a word, I knew. As if I’d played a wrong chord. I could almost tell what he wanted. I could almost hear the voice of Ferdowsi himself.

6.

One New Year our whole family took a bus to Qom— one of the holiest cities in Iran. When we arrived in the city it was like stepping back in time. This was a different kind of Islam. It wasn’t my father’s. It wasn’t even my mother’s. It was an Islam from fourteen hundred years ago. The bookstores only stocked religious books. There were no radios, no music. My nine-year-old sister tried to buy some glass bracelets at the bazaar, but the shopkeeper wouldn’t serve her. Because she wasn’t wearing a hijab. When he turned his back I broke the bracelets against the table. In the afternoon I was given time to explore on my own. I remember I was wearing long pants. I’d never worn long pants before, so I felt like a man. I made my way to the biggest shrine in the city. There was a huge crowd for the holiday. As I pushed my way through, the crowd began to sway and move. People began to shout all around me. Hats were thrown into the air. I couldn’t see what was happening, even when I stood on the tips of my toes. But suddenly the crowd began to part. If I’d been one step further back, it would never have happened. But a path opened up in front of me. And there he was. I’d seen his portrait every day of my life on the inside cover of my Shahnameh: Mohammed Reza. The Shah of Iran. He was not yet the famous Shah that he’d one day become. At the time he was still a young man. But on that day he seemed to me like one of the great kings of Shahnameh. I was a shy child. But something came over me, I couldn’t help it. I broke free from the crowd and began to follow him. He took off his shoes, I took off my shoes. He entered the shrine, I entered the shrine. This was my chance I’d never been so close to a king. I knew I had to do something, so I reached out. And I touched his coat. I touched the coat of a king. That night when I came home I looked at myself in the mirror. Ferdowsi describes Rostam as having the height of a cypress. And arms that could rip rocks from the side of a cliff. I took one look at my scraggly body, and decided I was much too skinny to be a knight. But my garden was the best, it was plain for all to see. So I decided I would become the Shah of Iran.

7.

In Shahnameh there’s one word that Rostam uses more than any other: Daad. Justice. Daad is a simple concept. It means that everyone gets what they deserve: both good and bad. Everyone gets a fair share. The Nahavand of my childhood was very poor. People would come to our door each day asking for a single piece of bread. It seemed unjust to me. So I decided I would not eat more than that. My mother begged and begged, but I would not do it. I decided that if I became king, every child in Iran would be given their fair share. But until then I should participate in their suffering. I had no idea how I would become king. In Shahnameh it seemed so simple. Good kings glowed with light. Their wisdom was plain for all to see. I was an optimistic child. I felt that if I could use my voice, and speak about Daad—then a path would open up before me. When I turned fifteen I went to boarding school in Tehran. It was nothing like Shahnameh. Half a million people lived there, and it was a time of great upheaval. A huge debate was being held over the nationalization of oil. The streets were filled with voices of every kind, and nobody could agree on the future of Iran. I realized that many people didn’t want the same things that I wanted, and for complicated reasons. At the end of each week I’d go to the house of a relative to pick up my allowance. His wife was the first person in Iran to have a cooking show on the radio, so sometimes I’d stay for dinner. They had a young daughter named Mitra. Her hair was cut short in the style of a famous American actor. One of her hands was crippled by polio. She was very shy about it, but it was never something I noticed. Back then most Iranian girls were modest and deferential, but not Mitra. And she argued with everyone: her friends, the help, her family, and me. One night over dinner I started speaking about the past greatness of Iran: who we were. Back in the days of Shahnameh. When I finished talking, Mitra was the first to speak. She said: ‘You talk about Iran like it’s a lion. But it’s a cat.” That was the year I discovered something new. There are love stories in Shahnameh too.

8.

There’s only one way for love to begin in a traditional society. With the eyes. At the dinner table Mitra disagreed with everything I said. If I said ‘red,’ she said ‘green.’ If I said ‘spice,’ she said ‘sweet.’ But there was something between us. I could see it in the eyes. It was like glancing at a beautiful mountain from afar. The mountain hasn’t been experienced yet. Its cliffs have not been climbed. Its flowers have not been picked. But you are drawn to its beauty, even at a distance. On her fifteenth birthday I got her flowers. It was winter. There weren’t many flowers during winter. So I went to an Armenian flower shop and got fifteen white carnations, with one red in the center. I was shy with my words, so I wrote her a long letter. I told her the story of the female knight Gordafarid, one of the bravest champions in all of Shahnameh. Gordafarid was a master of archery. No bird could escape her arrows. And she was beautiful: her face glowed like the moon. Her waist was cypress-shaped. Her hair was worthy of a crown. I told Mitra: ‘She’s just like you. Together we can do great things for Iran!’ Mitra hid the letter from her father. One night over dinner I told him about my plans to become king. I told him that I would use my voice, and speak about Daad. Justice. He said: ‘This boy is delusional! He’s living in a thousand-year-old book!’ He told me that Iran was a constitutional monarchy. And unless I planned to lead a coup, the highest I could rise was Prime Minister. He said that Iranians were too worried about survival to care about ideals. So if I wanted to be Prime Minister, I’d need to put away childish ideas and learn about the real world. A few weeks later I joined a club of students at my school who met each week to discuss politics. It was the youth chapter of a new party called the Pan-Iranist Party. The leader of the club was a medical student from the University of Tehran. His name was Dr. Mohammadreza Ameli Tehrani. But everyone called him by his nickname: The Siren.

9.

The club was called Niroo. The Force. There were ten of us. We were all so different. But we were like charms on a bracelet—united by our love for Iran. It was nothing important: we’d graffiti our slogans onto walls. We’d stand on busy street corners and try to convert people to our cause. But it felt so important. We felt like we were building a new Iran around us. We held our meetings in an attic. We’d check the street for spies before we went inside. I had one of the strongest voices in the group, so I’d open each meeting by reciting a hymn about loving Iran. We’d review our activities from the previous week. Then Dr. Ameli would lead us in long discussions about the meaning of Iran. Dr. Ameli was a nationalist. But it wasn’t a nationalism of expansion. It was a nationalism of preservation. A nationalism based on history and culture, with respect for all people. That’s one of the very first things he taught us: ‘What is true, must be true for everyone.’ We learned that the Persian Empire began when Cyrus The Great united a group of nomadic tribes in 550 BC. Many consider Cyrus to be the founder of human rights. Whenever he conquered a new territory, he outlawed slavery. He allowed everyone to live with their own language and religion. In the ancient world Iranians were known as Azadeh. Free people. It’s even in the Shahnameh. When one of our champions is mistaken for an angel, he says: ‘I come from Iran. The land of the free.’ Listening to Dr. Ameli speak about the foundations of Iran, we felt like we’d discovered something hidden. An Iran built on ideals. Rasti. Neeki. Daad. An Iran built on freedom. Azadi. During the final meetings of Niroo that I ever attended, we were joined by a girl named Parvaneh. She was a basketball player; and her voice was just as strong as mine. At the close of each meeting, we’d lead the group in the swearing of seven oaths. I don’t remember all seven, but I remember the final. To give our lives for Iran.

10.

Mitra loved anything beautiful. She kept countless notebooks. And on every page she’d paste something beautiful: a flower, a feather, a line from a poem. One time we went to a large antique shop, and the owner challenged us to choose the most expensive items in the shop. Mitra looked around the store and chose two that nobody else had noticed. The owner was shocked. He announced that those were the only two that were not for sale. She had a genius for beauty. It was one of her greatest gifts. But her greatest gift by far, was her memory. Mitra could memorize an entire poem after hearing it a single time. Her favorite was Hafez: The Prince of Romance. She’d memorized two hundred of his ghazals. And whenever she found a verse that she loved, she’d bring it to me to read. We’d heard our voices many times before in arguments. But it was different when we read poetry. There was a softness, a delicacy. When you’re reading a poem, you must find the Ahang. Melody. The instrument is your throat. And the words are the notes. Some you strike suddenly—with a bang. Others you unroll gently, like a bow being slowly pulled across the string of a violin. Every word has life. Every word has its own soul. The word roar has a soul. Khoroosh! And so does the word kiss. Booseh. We were married in the traditional way. It was a small ceremony at the home of Mitra’s father. On the morning of our wedding Mitra and I visited a famous photographer in Tehran. We took a series of photographs standing side-by-side. She was so conscious of her crippled hand, she found a way to hide it in every photo. But she’d never looked so beautiful. When the session was finished, I suggested one final photograph. I could tell the photographer was annoyed, but he agreed. And it’s the photograph that still hangs in our house today. Mitra is sitting on a chair. And I’m down on one knee, looking up at her, holding her hand.

11.

Before our wedding Mitra’s father gave her one final piece of advice: ‘Never let a man enforce his opinions on you.’ And she took it to heart. She was my opposite. My antithesis. The hardest for me to convince. She would tell me I was too optimistic. She’d say that I only saw the best in things, whether that be people, Iran, or Shahnameh. After our marriage I finally convinced her to read it with me. We’d just moved to Germany so that I could attend university. Each night when I came home from class, she’d lay her head in my lap and I’d read her a chapter. It was my second time reading the book all the way through. My first time as an adult. As a boy I’d always been drawn to Rostam’s feats of strength: his taming of Rakhsh, his defeat of the demon king, his slaying of the dragon. But now I noticed something else. Rostam lived by a code. He would not serve an evil king. He would only serve his ideals. Daad. Justice. Rasti. Truth. And most of all, Azadi. Freedom. Rostam would never sacrifice his freedom. The great champions of Shahnameh were more than warriors, they were vessels for our ideals. Even in the darkest times, even in the times of greatest danger, they lived by their code. I did my best to interest Mitra in certain parts. When I came to the story of the female knight Gordafarid, I quickened my pace. I filled my words with excitement: ‘The battle was nearly lost. Gordafarid’s commander had been captured on the battlefield. Her castle was completely surrounded by the enemy. Gordafarid tried to rally the men to fight, but none would join her. They wanted to stay behind the castle walls. They wanted to surrender. Gordafarid’s cheeks turned black with rage. She grabbed her bow and arrow, tied her hair beneath her helmet, and rode out to face the enemy alone. She stopped just short of the enemy lines, and like a lion she roared: Where are your champions?’ In the heat of the story, I peeked down at Mitra to see if she was scared. But she’d fallen asleep.

12.

She was brave in many ways. But there were three things that Mitra feared most: darkness, silence, and being alone. In Germany we’d take long walks through the countryside. Mitra couldn’t stand the quiet. She’d recite entire poems back-to-back-to-back. At the time she’d gotten into modern poetry. Her favorite poet was a young woman named Forough Farrokhzad. Farrokhzad was a modern poet. She wrote in free verse. She wrote from a feminine perspective. Religious society called her a ‘whore’ and a ‘slut.’ Because she wrote about everything. Including sex. By the time we finished Shahnameh I think I’d destroyed Mitra’s interest in the book. The book’s longest section is the historical section. Here the heroic nature of the prose fades. There are no more dragons. No more Rostam and Gordafarid. Here Ferdowsi writes about real people. He must stick to what is known. You can’t turn a real person into a mythic hero. That summer I took a road trip home to Iran. The Shah had just announced his White Revolution. It was a sweeping campaign of reform. Women were given the right to vote. Factory workers gained a share in profits. Agricultural estates were seized and redistributed to the sharecroppers who worked the fields. With one referendum the Shah gave more freedom to millions of Iranians. But not everyone supported it. When I arrived in Tehran the city was in chaos. Several buildings on my street were in flames. A cleric named Khomeini had come out against The White Revolution, and he’d ordered his followers to riot. Khomeini practiced a different kind of Islam. This was not the Islam of our fathers. This was not the Islam of the Persian Mystics. This was an Islam of cutting off hands, death for nonbelievers, and oppression of women. We thought these things were demons from our history. Monsters buried far in our past. But there’s a parable in Masnavi, where Rumi writes about a dragon frozen in a block of ice. The dragon seems to be dead. So the people place him on a cart and wheel him into the center of the city. They’ll soon discover that he’s still alive. He was only sleeping, waiting for things to heat up.

13.

In Germany we started a family. When our first daughter was born we named her Ahang. Ferdowsi uses the word a lot in Shahnameh. It means melody, but it also means willpower. Eighteen months later our son Maziar arrived. After the children were born Mitra said it was time to choose a normal profession, and secure the life that we had. At university I studied mechanical engineering. But wherever I am, I think of all of Iran. There were many Iranian students living in Germany, so I started my own version of Niroo called the Assembly of Kaveh, after one of Shahnameh’s greatest champions. Kaveh is a special champion. He was a normal man. An ordinary blacksmith. But he rallies the people to defeat Zahak—the most evil king in all of Shahnameh. Our meetings were held in the back room of a local tavern. The meetings were more cultural than political, each week we’d lecture on a different topic. But I was outspoken about my support for the White Revolution. We’d lost half our family’s land as part of the land reform, but still: I supported it. I wrote my father a letter. I said: ‘Today we can hold our heads higher, because there is more freedom in Iran.’ One day we were in the middle of a meeting when the door was kicked in. Two hundred angry men rushed into the room. They were mainly members of a leftist group, but they’d also been infiltrated by The Shah’s secret police, SAVAK. Their agents had been tasked with creating conflict between student groups. The men went around the room, knocking over furniture. One of them broke a coke bottle against the table, and wielded it as a weapon. I stood up from my chair and rolled my papers in my hand. I said: ‘Please, sit down. Let us discuss. Let us use our words.’ One of them was dressed exactly like Fidel Castro. He picked up a chair and jabbed its leg directly into my eye. Blood started streaming from my face. My friends picked me off floor and helped me to the basement of the tavern. After a few minutes a police car arrived to take me to the hospital, and I was loaded in the back. I began to lose consciousnesses. The last thing I remember was a horrible, sharp pain in my eye. Then everything turned to black.

14.

We began in darkness. Three hundred years after the Battle of Nahavand. The invaders had plundered the country. Caravans of riches were leaving day and night. There was a huge push to break our unity, to erase our identity, to make us forget ourselves. And whenever a conqueror tries to destroy a people, they begin with the language. Scholars were murdered. Books were burned. Entire libraries were razed to the ground. Whenever words were found, they were destroyed. A knight gathered all the texts that remained. And Ferdowsi stepped forward to weave them into a poem. In the prologue of Shahnameh he writes: ‘I am building a castle of words. That no wind or rain will destroy!’ Ferdowsi attempted to use only the purest form of Persian. He wanted to preserve the entirety of our language. All of our words. But it wasn’t just our language that he was trying to save, it was our story. Our wisdom. Our soul. Who we were. Ferdowsi drew from many different sources when writing Shahnameh. But one of the most important was The Avesta. The holiest book in ancient Iran. It included many of our oldest stories, from before the written word. In the heart of the book, away from the edges, safe from the sands of time, were the oldest words of Iran: the seventeen hymns of Zoroaster. They were three thousand years old. And they’re in the form of a poem. They tell the story of a battle between two great spirits: Ahura Mazda and Ahriman. Good and Evil. Light and Dark. Since the beginning of time these two spirits have been locked in a battle for the soul of the world. And every person must participate. There can be no spectators. There is always a choice to be made. Light or Dark. Good or Evil. Neeki or Badi. It’s a simple choice. But in that choice is an escape from destiny. A promise that the book is not yet written. There is still a role for us to play.

15.

After my injury Mitra said it was finally time to be realistic. She began to use the words I would hear for the rest of my life: ‘You’ve already lost one eye for your ideals.’ I’d always respond the same way: “I’ve still got one eye left. And I’d like to see the world for as beautiful as it is.’ When we came home from Germany I promised that I’d never leave Iran again. Not even once. Not even on vacation. The only job I could find was at a steel factory. It wasn’t my ideal position. But wherever I am, I think of all of Iran. It was my hope that I could gain some experience and spearhead an industrial policy for the entire country. Inside the house Mitra was queen. She wanted everything in our house to be beautiful. She’d make entire booklets of beautiful things that she’d clipped from magazines: one for couches, one for lamps, one for tables. Mitra chose all of the children’s clothing. Sometimes they’d miss their bus because she was so particular. And whenever she decided—it was final. I tried to teach the children to use their voice. I’d tell them: ‘If you disagree with what I say, use your words.’ But Mitra was the opposite. She wanted her word to be the law, and that also applied to me. We once went to a famous carpet store in Tehran. Inside there were many beautiful trees. When Mitra asked the owner how he kept them so green, he said that every time he finishes a kettle of tea, he pours the remains on the roots of the trees. From that day on, Mitra made me pour the remains of our tea on the roots of our trees. She’d send me out in the middle of the night to do it. I tried to appeal to her reason. I told her that it made no sense. It was nonsensical. But inside our home her word was the law. Only once did I make a stand. When our youngest daughter was born, Mitra wanted to name her Kakoli—it’s a beautiful little bird with a plume on its head. But I had a different idea. We argued about it for weeks. And in the end we made a compromise. We agreed to call her Kakoli. But her name, would be Gordafarid.

16.

When the children were old enough I started reading them Shahnameh before they went to sleep. The stories of Rostam were too violent. They’d cry and cry. So I started with the stories of Iran’s mythic kings. These were the first kings of Iran. They discovered fire, language, and law. Some of them spoke to animals. Others lived for hundreds of years and sat on floating thrones made entirely of precious stones. It’s not known if Ferdowsi intended to name his book Shahnameh. The Book of Kings. But the title fits. For as long as there has been an Iran, there has been a king. In 1967 Mohammed Reza held a coronation ceremony. By that time he’d already been king for twenty years. But he’d wanted his coronation to wait, until Iran was prosperous. And now it was. The Shah had come a long way since that day I’d first seen him in the shrine. He’d tightened his grip on power, and his popularity was at an all-time high. The White Revolution had been a massive success. Iran was rapidly industrializing. Millions of Iranians were lifted out of poverty. Hundreds of new schools and universities were built. And it was a time of great freedom. Iranian women had more rights than anywhere else in the Muslim world. They could vote, obtain a divorce, own property, and run for office. In the words of Saadi: ‘The homeland is where no one disturbs the other.’ In Tehran you could see women in mini-skirts standing next to women who were fully-veiled. On the day of his coronation The Shah rode to the palace in a golden carriage pulled by eight Hungarian stallions. As he passed the streets were filled with shouts of ‘Long Live The King!’ Trumpets blared. Guns fired. The Air Force dropped 17,532 roses from the sky. One for every day of his life. At the coronation a crown of diamonds was placed upon his head, and he took his seat on the famous Naderi throne. It was decorated with carvings of lions and dragons. And it was covered with 25,000 precious stones.

17.

We still took long walks together. Mitra hated walking through deep forests, they were too dark. She’d imagine that predators were hiding behind every tree. By that time I’d begun to organize the workers at my factory. I’d hold weekly meetings and speak to them about their rights, but Mitra wanted me to stop. She thought it was too dangerous to speak out in a closed society. The Shah had brought many freedoms to Iran, but there’s one place he stopped short: political freedom. No dissent was allowed. No criticism appeared in the media. And his secret police SAVAK had a reputation for violence. Many of his political opponents shared brutal stories of their treatment in prison. After our Niroo meetings Parvaneh became extremely anti-Shah. She was the basketball player; the one with the strongest voice. She married a fellow activist named Dariush Forouhar, and she joined the party he had formed. They wanted nothing less than full political freedom. And both of them went to jail several times for their views. Dr. Ameli tried to work within the system. He’d become a member of parliament, but when he spoke out against the king the Pan-Iranist Party was banned. The king saw himself as a king of old. He wanted to rule Iran with a single voice. One year I decided to write about the history of our factory. I saw it as a great example of the Iranian people coming together for a common cause. Forty thousand people were involved: materials had been contributed from local mines, a dam was constructed, an entire city was built for the workers. It had truly been a national project. I spent an entire year on the book. But before it could be published, it had to be reviewed by the secret police. They told me it could not be published unless it was dedicated to the leadership of the Shah. It was abhorrent to me. The Shah played a role, but the factory had been built by the people. By giving all the credit to one man—it takes away their authorship. I told them: ‘Write whatever you want. But take my name off it.’

18.

The Shah threw a celebration on the 2500th anniversary of the Persian Monarchy. It was the largest gathering of world leaders in history. He constructed a city of tents around the ruins of Persepolis, where Cyrus’s grandson Xerxes ruled the ancient world. 1500 Cypress trees were planted in the middle of the desert. There were vast carpets of petunias and marigolds. The Shah opened the ceremony with a speech at the tomb of Cyrus The Great. As he spoke, his voice shook with emotion. He said: ‘Rest in peace, for we are awake. In a troubled world, Iran still bears the message of freedom and humanity. Even in the darkest times, the torch thou lit has never died.’ The king was at the height of his power. Oil prices were at record highs. With each passing year Iran grew wealthier and wealthier, and the king gathered more power into his hands. Every New Year I would gather the children together and read from Shahnameh about the story of Jamshid—the fourth king of Iran. Jamshid was the greatest king. The wisest king. The Iranian people gathered around him in adoration, and built him a throne of sapphires, emeralds, and rubies. He taught men to build buildings. He taught men to heal the sick. He unlocked all the secrets of the world. And his throne began to float into the air. With each new gift to the people, it rose higher. And higher. And higher. Until one day it rose too high. Jamshid lost touch with the people. He could no longer hear their voice. He no longer wanted their participation. He gathered his advisors around him, and announced: ‘All good things come from me. I am the maker of the world.’ As soon as he spoke these words, his throne began to fall. With tears of blood he begged for pardon, but none was given. And the dread of coming darkness was his lot.

19.

It has always been my philosophy: wherever I am, I try to make the most of the responsibilities I am given. Managing a factory was not my ideal position. I had hoped to find a place where I could have more of a national impact. But I tried my best to improve the lives of the people nearest to me. I continued to hold meetings with the workers. I studied employment practices from all over the world, and drafted a policy of worker’s rights. It was very progressive for the time. But when I presented the document to the Department of Labor— it was approved for the entire factory. Five thousand lives were made better. In 1975 The Shah made an announcement that he was dissolving all political parties and combining them into one. He claimed that it was an attempt at unity, but it was abhorrent to me. A country cannot be ruled by a single voice. In the next election I decided to return to Nahavand and run for parliament as my own man. Mitra was against it. She told me that I was too honest for politics, too naive. She said: ‘Even if you win. You’re a single voice. The rest of the parliament will still be controlled by the king.’ Even my father didn’t want me to run. He didn’t think I stood a chance, and he didn’t want to see me get my heart broken. The king had to approve all candidates, and he’d chosen two of his closest allies as my opponents. One of them played volleyball with the king and empress. The other was Undersecretary of Education for the entire country. He was so confident of his victory that he’d already resigned from his previous position. After I announced my candidacy, he paid me a visit. He told me: ‘I want you to know. Everyone in government is supporting me. And this position has been promised to me.’ I told him: ‘I’m very happy for you. I have no intention of winning. But I am going to say what I have to say.

20.

Dr. Ameli helped me open a party office. He was an established man by then. But he took the time to come to Nahavand. I’ll never forget the speech that he gave. He said: ‘Now it is winter, the rivers are frozen, the trees are all dead. But soon green sprouts will burst from the soil. The air will fill with the songs of nightingales. And together we will say: 'Spring has arrived.' There were over one hundred villages in Nahavand, and I made the decision to visit every single one. My father loaned me his jeep, and I would spend all day on the road. Most villages had a central square, and that is where I would speak. I was a practicing Muslim; I knew the Koran front-to-back. But I never spoke about religion. I spoke about what needed to be done: better roads, better schools, fresh water. I spoke about justice. Daad. About an Iran where every person got their fair share. And I spoke about freedom. Azadi. I told them: ‘The king should not choose your candidates. All of Iran should be your candidates.’ In the first few villages only a handful of people came to my speeches. It was not customary for candidates to speak directly to the voters. My two opponents stayed in their homes and held fancy parties with their friends. But as I continued to speak, word began to spread. More people came, and then those people would go tell others. I’d always give my speeches around 6 pm. Some of the stores began to close early, so that the shopkeepers could attend. At first it was just a few. But by the end of my campaign, every single shop would close. The moment my jeep pulled into town, it would be met by cheering crowds. Hundreds of people would gather around to hear me. People as far as the eye could see. On the day of the vote I took the jeep for one final trip around Nahavand. I remember seeing young women, with babies on their breast, going to cast their vote. Later that night the results were announced on television. Early in the day people began to gather around my father’s house. When the vote was announced, the crowd erupted into cheers. Each of my opponents had gotten two thousand votes. I received over twenty thousand.

21.

After the election I took one more visit to Ferdowsi’s tomb. This time I brought my own children with me. It hadn’t changed much in thirty years, but I had changed. I had a better understanding of the sacrifice he’d made for his ideals. Ferdowsi worked for thirty-three years. Seven verses a day. A castle of words, that no wind or rain will destroy. While my children played in the gardens I stood quietly at the foot of his tomb. I ran my fingers across the stones. ‘In The Name of The God of Soul and Wisdom.’ Jan and Kherad. The two things all humans have. The wisdom to choose. And the soul to create. When I received the development budget for Nahavand, I called a meeting in the town’s biggest auditorium. Each village sent a representative. I told them: ‘God created the earth, the trees, and the waters—but after that he did not make a single chair. He has left the rest to us.’ I told them: ‘Organize a council, assess your own needs, make specific proposals.’ I’d only pay for things that could be seen, because I wanted no corruption in Nahavand. And priority was given to projects where labor was provided by the villagers themselves. I wanted them to get involved, participate. I wanted them to feel a sense of ownership. I wanted an Iran where everyone felt like the king or queen of their own country. Back then it was common for villagers to kiss the hands of government officials. I would not allow it. I told them: ‘We don’t need to do this anymore.’ If I was unable to stop them in time, I’d kiss their hand right back. There was one woman in Nahavand who lived in a tent. I promised her that I would not own a home before she did. I tended Nahavand like I tended my garden. I picked every weed the moment it appeared. I followed up on every call, every letter. My phone was never unplugged. My plan was to serve two or three terms, so that I could gain some experience and build my name. Then I’d bring my ideas directly to the people. What I could do for my garden, I could do for Nahavand. And what I could do for Nahavand, I could do for all of Iran.

22.

Dr. Ameli was elected to parliament in the same election, and was chosen by his peers for a leadership position. He was a unifying figure. A man without enemies. His words never cut. He attacked philosophies; never people. And he was one of the best speakers in parliament. He didn’t use slogans. He spoke with depth. And somehow, no matter how specific the policy, or how divisive the issue, he always came back to a place of unity. Our common destiny as a people. On the morning our first budget was presented Dr. Ameli approached me in the halls of parliament. He asked if I planned to give a speech. I told him I did not, because I had no specific objections. He leaned close to my ear, and with a soft voice he said: ‘Still, you must speak. To separate yourself from the system.’ That night I slept on a rug on the floor of parliament, and first thing in the morning I placed myself on the calendar of speakers. When my turn came I walked down the aisle toward the podium. My knees felt weak. There is a magnitude to speaking in parliament, a consciousness of history. I’ve never been a natural speaker. I’m never the one chosen to give a toast at parties. But if I believe a statement is true, I can say it. No matter how big the stage. Truth has power. Truth has a force. Niroo. It doesn’t come from the tongue, it comes from within. And the moment I take my place at the podium: it’s like a spring has been sprung. That day I spoke about justice. Daad. I said that justice in society begins with justice in our budget. There was a proposal in the budget to build a new telephone system in one of Tehran’s nicest neighborhoods. I reminded the parliament that there were entire villages without a single phone. I said: ‘Before we give the wealthy a phone by every bedside, let us give a phone to every village.’ It was one of the most forceful speeches I’ve ever given. But there was no mention in the media; criticism of the government was not allowed. I at least wanted a copy for my own records. There was a person in parliament who transcribed everything, so I asked them for a copy of my speech. But they told me it was not allowed. They would not even give me my own words.

23.

Each night when I came home from parliament I’d find Mitra ready to go out. And no mattered how tired I felt, off we would go. She always looked perfect. She stayed current with all the latest trends. Every few months she’d have her hair cut in the style of a different American actress. I loved having her by my side in social situations. I was horrible at parties. I could never think of the right thing to say. If I tried to make a joke, people would tickle themselves to laugh. But not Mitra. She was spontaneous, she was funny. Words came from her like light from a lamp. And she could speak to anyone. There were never any formalities. No warm-up. She’d talk to every person as if she’d known them her entire life. We’d go to gatherings with ten or fifteen of our friends; often Dr. Ameli would be there. As soon as Mitra walked in the room the silence would end. At some point in the evening the conversation would always turn to politics. And the moment I began to debate an issue, Mitra would take the other side. She would team up with anyone against me. The person never mattered. The topic never mattered. She never wanted to get me started, so she’d always shut me down. It’s how we’ve been our entire lives. I’ve been the gas, she’s been the brakes. I thought about her every time I wrote a speech. She’s always been my antithesis. The hardest for me to convince. It could sometimes seem like her main purpose in life was to oppose me. To the outside world our love made no sense. We seemed so far apart. But there are many types of closeness. And some the world will never see. We still read poetry together. Mitra still trusted me to find the melody. There was one poem called ‘Sin,’ by Forough Farrokhzad. It scandalized religious society; everyone was talking about it. But it was one of Mitra’s favorites, so I’d memorized the entire thing: I sinned a sin full of pleasure / in an embrace that was warm and eager / I sinned wrapped in arms / hot, hard, and avenging / in that dark and silent seclusion / I knew his secrets / my heart quivered in my breast / in answer to his hungry eyes.

24.

One afternoon the empress and prince attended a session of parliament. It was an important day. Everyone was hoping to make a strong impression, and I’d prepared a speech especially for the occasion. I was the last speaker on the schedule. The Speaker of Parliament saw me approaching the podium and tried to wave me off. When I kept coming, he hurriedly adjourned the session. I think some of my colleagues viewed me as an annoyance. I’d developed a reputation for speaking my mind. And whenever I could speak, I spoke. I gave a speech on every budget, every proposal, every vote. The topic was always different. But the theme was always the same: Daad. Justice. The word that appears most in Shahnameh. Everyone gets what they deserve. One day I gave a speech saying I’d been informed that Iran’s highest-ranking admiral had used a battleship to import Italian furniture. I asked how we could allow such corruption, from a man with a breast full of public service medals. The crowd was silent. It was unheard of to criticize the military, because it was in the hands of the king. But I wanted to show that I was not afraid to speak. So that other Iranians would feel free to share their thoughts. My words were never heard in the media. If there was ever a mention in the newspaper, it would only say: the senator from Nahavand gave a speech. But still, I spoke. I always had hope that I’d find a way to be heard. There is an Iranian proverb about ‘words that fly.’ It says that if words are false, if they are self-serving, if they come from ambition: they will never fly. Even if they’re shouted from loudspeakers. Even if everyone says them at the exact same time: they will soon be forgotten. For they have no soul. They have no jaan. But if a person can find the right words. If the words have ahang, if the words have kherad, if the words have rasti-- they will grow wings. And they will fly. Even if they’re censored; they will fly. Even if they are silenced; they will fly. Even if they are buried deep in the ground; they will still fly. And they will reach the doorstep of every household.

25.

There is a game that Mitra and I would often play. One of us would recite a verse from a poem. Then whatever letter that verse ended with, the other person would think of a verse that began with that letter. We’d go back and forth until someone got stuck. And Mitra could not be beaten. Her memory was a library of Persian poetry. When our children were older she applied to the literature program at the University of Tehran. It was a very selective program, but she received one of the highest possible scores on the admissions test. Some mornings I’d drop her off at school on my way to parliament. She’d have me drop her off down the street, because she didn’t want to be seen with a parliamentarian. The college campuses in Tehran had become a hotbed of political protest. With his White Revolution the king had provided free education to the children of Iran. Now those children were grown, and they wanted a say in the future of their country. Many wanted more freedom. They wanted truly free elections. They wanted an end to censorship, an end to political persecution, an end to SAVAK. Others thought the king had brought too many freedoms to Iran: the capitalism, the tight clothes, the violent movies. It was too much, too fast. They wanted a return to tradition. And Islam became a rallying point. But this was the Islam of our fathers. An Iranian Islam. The Islam of Rumi. The Islam of Hafez. During our next break from Parliament I visited a bookshop. The owner reached beneath his desk and pulled out a book by Khomeini-- the cleric from Qom who had incited the riots in Tehran. Khomeini had been sent into exile by The Shah, but he still had a large following in the country. His speeches were smuggled into the country on cassettes and sold in the bazaar. In his book he called for an Islamic dictatorship. He talked about returning to ‘the source’ of Islam. Sharia Law. It was an Islam from fourteen hundred years ago. An Islam of cutting off hands, oppression of women, and death for non-believers. He said that ‘Islam provides a law for every aspect of human life.’ But he did not say how the law would be enforced. That he said, would be figured out later.

26.

Mitra was the oldest in her class, but all the younger students loved her. She knew all the latest in culture: the movies, the magazines, the trends. Every night when I came home she’d always be up listening to tapes. The seventies were a golden age of music in Iran: Googoosh, Delkash, Marzieh, Aslani, Haideh, Shajarian. And Mitra had many of their songs memorized. She was a great student. During the second year of her program she was chosen to study under one Iran’s top Shahnameh professors. It was the closest she ever came to understanding me. One day in class the professor told her that every society needs a few idealists, because they’re the ones who move society forward. Often I would help with her homework, and it helped me view Shahnameh from a more academic perspective. Ferdowsi uses the mythic kings as placeholders for periods in Iran’s history. When he writes that Jamshid ruled for seven hundred years, he means that it was a time of great freedom and culture in Iran. But when Jamshid loses touch with the people, a period of terror and oppression follows. The throne is taken over by the Serpent King Zahak. In Shahnameh Zahak is the embodiment of darkness. He cares only for his own power. Two giant snakes grow out of his shoulders. The devil promises Zahak that he will stay in power, as long as he feeds the snakes with the brains of young Iranians. It had to be the brains of the young. Because young people are the ones with energy. They’re the ones with courage. They’re the ones that can overthrow the regime. One day twenty students at Mitra’s school entered the cafeteria wearing masks, and began to forcibly separate men and women. They physically assaulted any women who were wearing make-up or Western clothing. On the way out they scattered pamphlets on the floor, warning that all women should adhere to Islamic guidelines—or there will be consequences. An atmosphere of fear began to spread across the campus. Mitra began wearing a hijab to school. She chose a beautiful white one, made of silk.

27.

One morning I was called into the Speaker’s office along with another colleague. We were told that he’d received a call from the king’s office, and the king needed our two votes on an upcoming issue. My colleague was silent. But I replied: ‘I cannot do it. If I was a soldier of the king, I’d crawl across the floor. But I am a representative of the people.’ When I looked over, my colleague had tears in his eyes. Nobody disobeyed a direct request from the king. But Iran was a constitutional monarchy. And that was supposed to mean something. When the king’s policies served Iran, I was the first to support them. But a country cannot be ruled by a single voice. Even if that voice is wise, it must be questioned. Ideas must be debated. New voices must be brought to the table so that the ideas can become even better. I knew the parliament was a corrupted system. The way to advance was to support the king. But I wasn’t there to be part of the system. I wanted to scream Azadi. Freedom. One afternoon I received word that the king would be making a trip to Nahavand, and that my presence was requested at the airport. I was excited for the visit. I searched Shahnameh for the perfect quote to greet him with. I chose from one of my favorite stories: the story of Rostam and Esfandiyar. In this story Rostam is a much older man. He’s served many kings. But when the current king turns oppressive, Rostam refuses to obey his commands. The king sends his son Esfandiyar to arrest Rostam. Esfandiyar has no desire to fight. He promises Rostam that the king only wishes to set an example. He says: ‘Please, just let me bind your hands.’ He promises that he’ll immediately be released. He promises Rostam all the riches of the kingdom, if only he’ll allow his hands to be bound. But Rostam will not. Because he would never sacrifice his azadi. Here Ferdowsi shows his genius. The dialogue is rich. The men dine together. They share wine. They flatter each other. Each man does everything to persuade the other to change his mind. But their fate was already written. They would battle to the death. Because one could not disobey his king. And the other could not disobey his code.

28.

The king loved Iran. And I believed him when he claimed that it was his dream to have a more open society one day. With a truly free press. And truly free elections. But he didn’t think Iran was ready. It was fear. So many foreign powers were trying to control Iran. The country was full of spies. He’d already survived two assassination attempts, and he saw enemies everywhere. I never viewed myself as an enemy of the king. There was only one thing I wanted. It was the same thing I’d wanted since I was a little boy, when I saw him for the first time. When I touched his coat. I wanted him to be a good king. I wanted him to respect the constitution. I wanted him to involve the people, and hear our voice. On the day of his visit I was excited to welcome him to Nahavand. I wanted to show him that we were trusting the people to make their own choices, their own decisions. I arrived early to the airport. The king’s handlers explained how the welcoming ceremony would proceed. I was to stand on the tarmac about fifty meters from where the king’s helicopter was supposed to land. He would speak to me first. And then he would go on to speak to a crowd of dignitaries gathered behind me. I walked out to my assigned spot. I was out there all alone, with a crowd of fifty people watching. I had my quote from Shahnameh ready. It’s from the moment that Rostam welcomes Prince Esfandiyar. He says: ‘Blessed is your throne. And blessed are the people of Iran, for they are the guardians of its future.’ When the helicopter landed, the king stepped out. He gave a quick salute to his military escort. And then he began to walk my way. I had my words ready, but I did not get to speak them. He did not stop. He did not slow down. He didn’t even look me in the eye.

29.

The riots began in Qom. One day Khomeini gave a speech saying that the moment had arrived for a true Islamic revolution. And that it was the duty of all Muslims to oppose the monarchy. The rioters targeted anything they deemed anti-Islamic: cinemas, liquor stores, shops selling Western clothes. When the police tried to crack down, a few of the rioters were killed. Khomeini declared the men to be martyrs, and forty days later a public memorial was held. Huge crowds came out. And the rioting began again. It was as constant as the beat of a drum: riots, deaths, memorial. Riots, deaths, memorial. Every forty days there would be another wave. And with every wave the destruction would grow. Eventually the riots spread to the capital. Many mornings I would walk to parliament because the traffic was so bad. One morning I was forced to take a different route entirely, because rioters were destroying a liquor store. They were breaking hundreds of bottles in the street, and the gutters were filled with liquor. My colleagues in parliament were nervous, but I was optimistic. I thought this might even be an opportunity for us. Our entire careers we’d been in the opposition. We often spoke against the king’s policies. Now the people were mobilized. They were in the streets. They were looking for an alternative. Maybe this would be the moment that the king would finally hear the voice of the people. Maybe this would be the moment for us to have a true constitutional monarchy. Khomeini wanted to bring Iran back to the dark ages. But I knew that Khomeini didn’t represent the Muslims of Iran. Iran had been Islamic for one thousand years. We were the nation of Rumi. The nation of Hafez. These fanatics did not represent our religion. I even gave a speech from the podium of Parliament where I quoted the Koran. It was the words of Allah himself: ‘Those who are furthest from evil, are closest to me.

30.

We were at the eighteenth birthday party of our daughter Ahang when we learned that a crowded movie theater had been set on fire in the town of Abadan. The arsonists had locked the exits from the outside, and four hundred people were killed. It was the largest act of terrorism in the history of Iran. Later it would be discovered that the arsonists were religious fanatics. But Khomeini was able to convince much of the country that the fire had been started by SAVAK, at the order of the king. The riots continued to grow. And the king began to panic. He called for the formation of a new government and fired his ministers. He wanted to replace them with upright people. People who could inspire confidence. People who could not be corrupted. And there was one member of parliament that was trusted most of all. He lived in a simple house. He drove a beat-up car. Nobody could question Dr. Ameli’s integrity. The king asked him to join the new administration as Minister of Information. In his new position he would be responsible for investigating the Abadan fire. If he discovered something that implicated Khomeini, I knew he would become a marked man. I drove to his office. I begged him to turn down the position. I told him: ‘Things have become too dangerous. Let’s stay low, let’s keep in our bunker. Once things have calmed down, we can reemerge. We can take a stand and make our case to the people.’ Thirty years earlier we had sworn an oath, to give our lives for Iran. The years had changed him in so many ways. There was white in his hair now. He was a respected leader. He’d written and spoken on every facet of Iran’s society and history. His thoughts had evolved. His policies had evolved. But his ideals had never changed. Every choice he made, he made for Iran. Every choice. He listened politely while I made my case. He knew. Deep in his heart he knew. He knew even better than I did. If something happened to the king, he was done. He’d have no protection. He’d have no support. But he had already made his decision. He was going to serve.

31.

One of Dr. Ameli’s first acts as Minister of Information was to bring cameras and microphones into parliament. For the first time ever, our speeches would now reach the ears of ordinary Iranians. During the first recorded session I gave a speech. I spoke about the same things I always spoke about. I spoke about daad. About every Iranian getting their fair share. I spoke about azadi. About every Iranian having the chance to participate in the future of their country. For the next week our phone at the house rang off the hook. People were calling me to thank me for my words, people I didn’t even know. But by then it was too late. Khomeini had grown too powerful. So much of the country had received their education in mosques. They viewed him as a savior; they thought a true Islamic revolution was coming. Opposition groups could sense the wave building, and they rushed to align themselves with Khomeini. They thought that they could mix in their own ideology with his views. They thought they’d be able to ride the dragons back, and direct his fire. Even many of the liberal groups were siding with him. Khomeini had been giving interviews. He was telling reporters that he wanted a democracy. He was saying that he would protect the rights of women, and people believed him. He would later claim that Islam allows lying during times of war. One week a rumor spread across the country that Khomeini’s face would be visible in the next full moon. Hundreds of thousands of people went to their rooftops. And hundreds of thousands of people, even educated people, reported seeing his face. On Ramadan nearly a million people marched in Tehran against the king. Our house was on one of Tehran’s main boulevards, so I stood in the doorway to watch the crowd pass. Many were students. They were joyful. They thought that freedom was finally coming to Iran. But the crowd was also filled with young religious men. They were dressed all in black. They would take a few steps, kneel, pray, and then they would rise and do it again. It was like a river, moving in one direction. And Iran was a leaf, floating on top.

32.

In the end the king turned against his own friends. One day a colleague approached me in the halls of parliament. She was married to a former minister, and the king had just thrown her husband in jail to appease the mobs. She asked me what I thought was going to happen. I answered with a quote from Shahnameh: ‘Tomorrow I will calm your fear.’ Even then I still had hope. I thought we still had time to save the country. But those were the end days. On the Friday after Ramadan there was a huge protest in one of Tehran’s main squares. The army panicked and fired machine guns into the crowd. One hundred people were killed, and that night one hundred fires raged in Tehran. Strikes began to hit the country. Everything shut down: schools, factories, air travel, even the oil industry. The lifeblood of Iran. The country became like a paralyzed man, gasping for its final breaths. In October the king went on television. It would be his final speech to the Iranian people. By then he was suffering-from late-stage cancer. He was a very sick man. He apologized for past mistakes. He said: ‘I am the guardian of a constitutional monarchy, which is a God-given gift. A gift entrusted to the Shah by the people.’ He said that he had finally heard our voice, but it was too late. The people had stopped listening. The king only had one option left.. His generals were still loyal. He still controlled the military, and there were half a million men under arms. He could fight. He could hold onto power, but only if he spilled the blood of Iranians. He had a choice. There’s always a choice to be made. Three months later I was listening to Mohsen Pezeshkpour give a speech from the podium of parliament; he was the founder of the Pan-Iranist party. In the middle of his speech, a messenger handed a note across the podium. He read the note, then over the microphone we heard him ask loudly: ‘Where did he go?’ The crowd let out a gasp. We knew then, the king was gone. The flag had fallen. The day was lost. And there’d be no more role for us to play. That’s the problem with kings. It’s like a tent with a single pillar. And when you take out that pillar—everything collapses.

33.

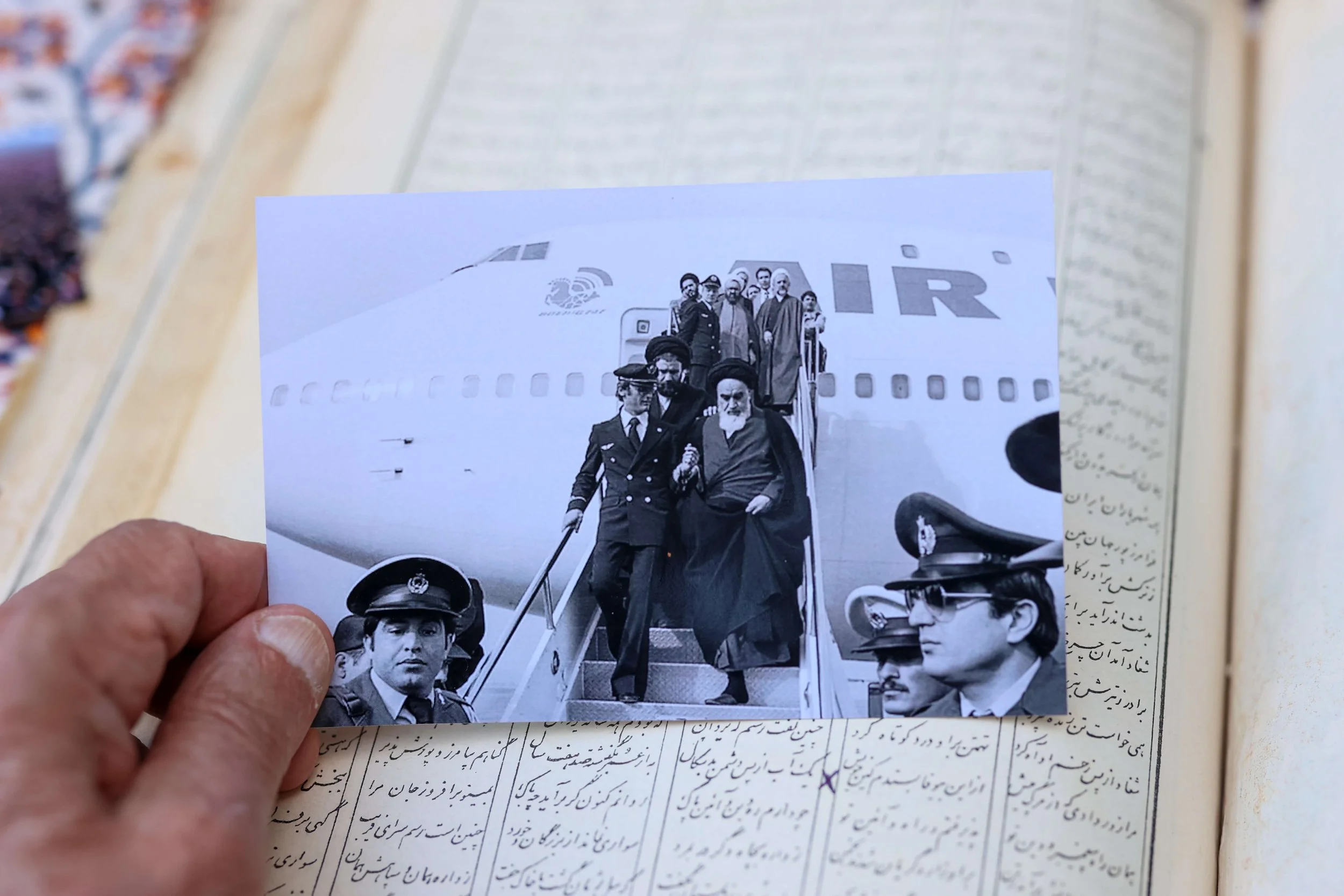

Things were quiet in the days following the king’s departure. I remember walking out on the sidewalk, and seeing people gathered in groups. They were talking about the new Iran. They were discussing the form it should take. Some wanted democracy. Others wanted socialism. Others wanted an Islamic government. But everyone assumed there would be a discussion. There’d be a debate, and everyone would get a seat at the table. Everyone’s words would be heard. On the day Khomeini’s plane landed the road from the airport was lined with hundreds of thousands of people. I hadn’t completely lost hope. The king was gone. But we still had a government, a parliament, a constitution. The only thing new was this man. Maybe he’d been telling the truth. Maybe he truly did want an open society. Khomeini had surrounded himself with liberal advisors. Maybe he’d allow them to run the country. Maybe he’d go to Qom and study his books. The parliament decided to form a small delegation to meet with him; to find out his plans. Since I’d been such a vocal critic of the king’s policies, it was decided that I should go along. Khomeini had taken up residence in a school building directly behind the parliament. When we arrived we were escorted into an empty classroom. There was no furniture. It was clear that people had been sleeping there, because pillows and blankets were piled against the wall. After five minutes Khomeini entered the room. He was dressed all in black. We told him that we were hoping for a peaceful transition of power. One that kept the constitution intact, and the parliament in place. We presented a list of ministers that we thought he would approve. He listened in silence. There was no response. There were no questions. It was clear that he had no need for our participation. Power was in his hands. When we finished making our proposal, he asked us to deliver two messages. One: he wanted us to tell the military that they had his full support. And two: that no one would be harmed, except for the king. Later he would claim that lying is allowed in times of war.

34.

The revolution officially began on February 11th, 1979. The military announced that they would no longer resist, and Khomeini’s forces took control of the weapons. That morning a bullet came through our window and landed in the wall above our bed. The country became like a house in an earthquake. Everything was scattered and there was nowhere to hide. The streets were barricaded with big bags of sand. Behind them were men holding automatic weapons. The executions began on the roof of the same school building where we had met. First the generals were executed. A few days later it was the Prime Minister. Then several powerful members of parliament. Khomeini would walk out afterward to inspect the bodies. Our house was next to the prison where members of the king’s former government were being held. Every morning we’d wake to the sound of the firing squads. Gordafarid was ten years old at the time. She was scared by all the gunfire, so at night I’d read to her the story of Gordafarid from Shahnameh. When the men refused to fight, Gordafarid tied her hair beneath her helmet. She loaded an arrow into her bow and rode out from the castle to face the enemy alone. She stopped just short of the enemy lines, and she roared. She roared like thunder! ‘Where are your champions? Who would dare to fight me?’ Only the enemy commander had the nerve to face her. They fought with fury. The battle burned, the rain of arrows, the spark of swords. Neither champion could strike a fatal blow. Then in the heat of the battle Gordafarid’s helmet was knocked to the ground. Her face shone like the moon. And her hair, her hair was worthy of a crown. The commander was stunned. A woman! It was a woman! He turned to his men, and screamed: ‘With women such as these, who would dare? Who would dare to face them?’

35.

Every morning we’d wake to the firing squads. When the newspaper arrived later that morning, it would show photographs of the dead. An atmosphere of fear spread across the country. It wasn’t just the killings. It was the manner of the killings. It was random. It followed no law. Revolutionary tribunals were formed to deal with enemies of the regime. Sometimes there wouldn’t even be a trial. Khomeini appointed an executioner as one of the judges. A bus would arrive at his court. He’d let one person pass, then hold the next. When the entire bus had been emptied—the people who were held back would be executed. Everyone had heard about it. When violence is random, when there is no law, when there is no daad, everyone thinks: I could be next. People grow fearful. They grow silent. And that’s exactly what the regime wanted. One month after the revolution, there was the first protest against the regime. It happened on International Women’s Day. Thousands of women took to the streets to protest the mandatory hijab. They called for the freedom to choose. Azadi. They screamed their slogans in the streets. But by that time the regime had taken over the media. The protests weren’t mentioned anywhere. Then there were the police—the people who were supposed to defend them. They fell on the women like savages, beating them with batons. Calling them ‘whores’ and ‘sluts.’ Bystanders looked on in fear and silence. Nobody tried to defend them. No one spoke a word.

36.

The religious fanatics were less than ten percent, but you couldn’t tell them apart. They looked like us. They spoke the same language. They did what no invader had been able to do for three thousand years—erase our nation, our culture, our connection to the past. But they did it from the inside. In the beginning things were relaxed. The first Prime Minister was a pious Muslim, but he was an educated man. A thoughtful man. Mitra attended an event where he was speaking, and his wife wasn’t even wearing a hijab. But the clerics slowly worked their way into government. And the more they got power, the more the environment became closed. Cinemas were shut down. Music was banned from television. The poetry of Forough Farrokhzad was banned. It’s not that Mitra promoted Khomeini, but she defended him. She’d say that the king wasn’t innocent either. She claimed that she liked the hijab. She felt that it was a symbol of modesty, and respect for tradition. At the time I was more religious than Mitra. I couldn’t make her understand: the problem isn’t Islam. There is nothing wrong with hijab. But there must be azadi. There must be the freedom to choose. I think Mitra only took the other side because she wanted to discourage me from speaking out. The environment had grown very dangerous. Dr. Ameli had gone into hiding. The regime was looking for any reason to go after people. They’d sent representatives to Nahavand looking for corruption, but they could not find a thing. One day Khomeini ordered every member of parliament to pay back their salaries. There were two dollars in my bank account; I had no idea what I was going to do. But my former colleagues in the opposition petitioned for an exemption. They wrote letters, arguing that we’d been critical of the king’s policies. And at the last minute an exemption was granted. One of my colleagues requested a meeting with the head of the Revolutionary Council, to express his gratitude. He asked me to come along for support. I didn’t want to do it. I didn’t feel any gratitude at all. I’d done nothing wrong. It would have been unjust to take my salary. But he begged me to come. He promised that I would not need to speak.

37.

The meeting was held in the office of the former speaker of parliament. He’d been executed four weeks earlier. It was an office I’d been to many times before. But everything beautiful had been removed: the paintings, the carpets, the furniture. In the center of the room was a single table, and at its head sat the leader of the Revolutionary Council. He was the man ultimately responsible for deciding the fate of the regime’s enemies. My colleague groveled. He read a prepared statement. He thanked the man for his wisdom. He thanked him for allowing us to keep our salaries. It was too much, it was difficult for me to watch. Then when he finished his remarks, he motioned to me and said: ‘Mr. Zafari would like to say something.’ I had nothing prepared. I could have just thanked the man. But when I know there has been an injustice, I must speak. It’s like a sword piercing my body. I feel the heat, I feel the pressure. I have to let it out. That’s the thing about ideals. Daad. Neeki. Rasti. Azadi. They depend on us. They only exist when we are living them. That’s why its so important a code. No matter how great the temptation. No matter how great the fear. If you abandon your ideals in the face of fear, they cease to exist. But the fear will stay with you. It will break you. Every day it will remind you: you’re not who you thought you were. And I’m not ready to lose the rest of my life to a single moment. There was a burnt match lying on the floor next to my foot. I picked it off the ground. I looked the leader of the Revolutionary Council in the eye, and I told him: ‘Two people suffer from every injustice: the oppressor and the oppressed. So maybe you should be thanking us, for not allowing this injustice.’ Then I held the burnt match in front of my face. ‘Even if you begged,’ I told him. ‘I would not even give you this burnt match.’

38.

I could not find it anywhere. The Iran of Shahnameh. The Iran of Cyrus The Great. The Iran of Rumi, Hafez, Saadi. The Iran of our mothers and fathers. The Iran that I had loved since I was a little boy—it had no use for them. They didn’t care about our culture, our history, our ideals. One day Khomeini gave a speech saying that nationalism was against Islam. He said that we should be a nation of Muslims, not a nation of Iranians. The Lion and the Sun were removed from our flag. Two of the oldest symbols of Iran. They were replaced by Arabic writing. One by one our institutions were dismantled. Soon the only things left of the republic and constitution were a mere name, an empty box. I took one final trip to Nahavand, three months after the revolution. It was like doing a survey. These were the people who trusted me most. Nobody could say that I’d ever wronged them. I wanted to speak with them freely, and share my thoughts. I wanted to see if they grieved along with me. Normally the moment that my car arrived into town, the news would spread like wildfire. People would gather at the house of my father. It had a very large salon. People would come and go as they pleased. They’d come in excited, passionate, sometimes angry. They’d be critical. They’d debate me. Everyone had something to say. But this time only a small crowd gathered. And I was the only one who spoke. I shared all of my concerns: that we were losing our ideals. We were losing Daad. We were losing Neeki. We were losing Rasti. We were losing Azadi. But everyone just listened in silence. They knew my words were true. They knew better than me. But it was fear. They were silenced by fear. There is a famous parable of Saadi about a caravan of one hundred merchants crossing the desert. Their camels are loaded down with riches. In the night they are overtaken by two bandits, and robbed of everything. Afterwards they are asked: ‘How could it possibly happen? There were one hundred of you, but only two of them.’ They replied: ‘Yes. But those two were together. And we were alone.

39.